A warm welcome to new subscribers. I’ve included links below to the previous parts of Forest Hydrology:

To begin, in my previous pieces on forest hydrology I mentioned the dangers associated with extracting trends from short term studies and how longer studies usually completely invalidated those apparent trends. I then went on to talk about how here in Coed Y Brenin we were experiencing a move towards drier spring and early summers. Then along came 2024...

above: temperate rainforest. An old oak surrounded by conifers. Note the prevalence of mosses, a testament to persistent high humidity.

First, apart from the rainfall data I collected, evidence for the apparent trend towards drier spring and early summer was apparent in the consequences of that lack of moisture at critical times of the year. Most notable, as in most noticed, was a considerable reduction in the number of midges. Previously appearing in vast hordes, usually in two waves, the insatiable demand of these tiny terrors for mammalian blood was so overwhelming as to drive both people and animals to shelter at certain times of the day. Visitors and students from Scotland who were familiar with these fearsome creatures often remarked that ours were worse than theirs...

As a small clearing in a large forest, we provided one of the few open areas with mammalian occupants for some distance (that's us as well as the various livestock) and hence we were well liked. One consequence of this vast, flying cloud of protein was swallows, two or three pairs nesting every year, raising two and occasionally squeezing in three broods of midge devouring chicks- the more the merrier. The reappearance of swallows each year was greeted with glad shouts of recognition as they darted and dived through their aerial landscape of currents, eddies and temperature gradients1.

The decline in swallow numbers corresponded to the decline in the midge population and about ten years ago we were able to be out at dusk with only minimal bites suggested something was changing. Six years ago, after going from three nests down to just one, the swallows turned up as usual, flew wildly about, in and out of their usual nesting haunts and then left. No swallow chicks that year because of insufficient numbers of midges and none since then.

One or two swallows, sometimes more, will appear as usual each year to make exploratory, open-beaked flights but presumably fail to find the requisite quantity of prey to rear young and sadly, they leave for midgy-er air spaces. The midge population continued to decline as the dry springs and early summers impacted on their crucial breeding periods. We have been able to work outside at any time of day, or indeed night, without suffering more than the odd bite. Then along came 2024...

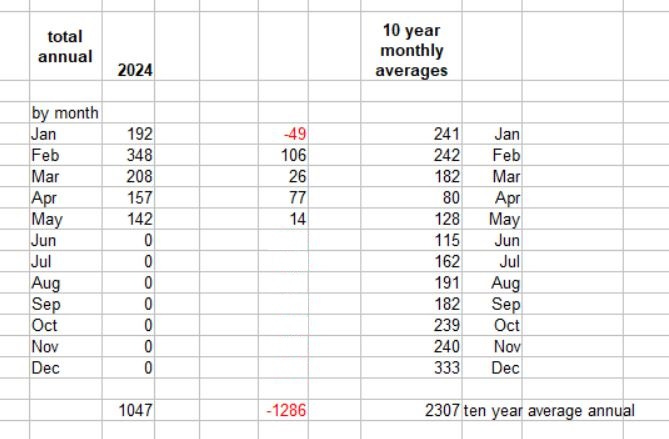

above: rainfall figures for 2024 so far showing above average rainfall for the last four months.

Our rainfall figures for 2024 so far, up to the end of May, show clearly that apart from a slightly drier January, every month has been wetter than the ten year average, not a lot, but sufficient and at the right times during the year to produce a resurgence of midges, certainly not in the vast quantities of the 1980s but enough to once more make working outside at certain times of day at least mildly irritating and occasionally downright frustrating. Coupled with this, is the reappearance of a pair of swallows who have been hanging about for much longer than in the last few years. Whether they will decide the midges are in sufficient numbers to support a brood or not remains to be seen.

Looking at the figures, the quantity of rain above the ten year average has come down in May so it may well be that we will still see drought and an increased fire risk as the summer rolls on. For now I comfort myself with the thought that though the wet weather has been disappointing for gardening (as well as the midges, slugs have reappeared in destructive numbers) and other outside activities, at least the forest is very unlikely to burst into flames at the moment.

So, I raise my hands, I fell into a trap of my own making and judged that just because something had happened for a few years, this year would be the same. Duh! Its important to remember that here in the UK and especially in the north west of Cymru, we actually have weather, as in a constantly changing interaction of complex systems of climatic cycles, ocean currents and fluctuating jet stream, to name a few. All go then, with occasional periods of stability that lull you into a false sense of security. Ho ho! I forgot my own Taoist mantra, “change is the only constant”.

There are a couple more things I would like to draw out of the studies2 of Dr. Graham Hall3 relating both to Coed Y Brenin specifically and conifer plantations more generally.

Most water in the UK is stored in the soil, far more than in lakes, rivers and reservoirs and as part of his work Graham made several attempts to measure the movement of water in and through soil, including one such study here at our place. This involved cutting a face into a steep bank to expose the soil profile and inserting thin, rigid, plastic sheets at each change in soil horizon to intercept water as it sank through the profile after a rain event. Each sheet was angled slightly downwards and outwards from the face of the cut to feed into a sloping gutter that deposited the water into a rain gauge at the end of the gutter to record the timing of the flow. The whole face was then covered with plastic sheeting to stop any rain getting in and interfering with the results.

above: me looking very practical by the site of the soil through flow study.

above: cutting the profile. The photo doesn’t do justice to the quite strikingly different colours of the various horizons, marked as follows:

dark humus rich surface horizon (top soil)

brown earth, with some iron accumulation at the base

very rocky horizon, with open cavities which can carry a lot of subsurface flow during storm events.

orange clayey material with few stones, probably glacial till.

above: the profile with inserts, gutters and gauges fitted, ready to go. The whole thing was then shrouded in plastic to keep rain out.

Measurements were very interesting, in general confirming what many of us already knew or conjectured. Following a rainfall event it could take something like six hours for water to flow down through the various soil horizons and appear at the lowest capture site. However, the longest time was taken to soak through the top soil, something like five hours or so of the total time. Some of the lower soil levels, despite being much deeper than the topsoil, were incredibly porous and water more or less flowed straight through them. It is the top soil, filled with life and organic matter, that hangs on to water for the longest time and hence is the biggest temporary storage for water in landscapes. So the more we can increase the depth and life of that top soil, the more water we can store in the system.

A further interesting observation was that in heavy rainfall events, the water table rises sufficiently to impede the downward movement of water, resulting in increased flows through the soil at shallower levels. Here at Penrhos, this can result in issues, where water appears at the surface, usually on a slope, moving higher up the hillside. In extreme rainfall events we have even seen water on our hillside spurting up out of mole hills.

Graham mentions in his study that results from the Penrhos measurements are particularly interesting because the instances of high volumes of shallow through-flow correspond exactly with later periods of extensive flooding of agricultural land around the head of the Mawddach estuary, some 5Km downstream. Monitoring the shallow through-flow could then provide an early warning system for later flooding downstream.

Considering the significance of the top soil in water storage I'll mention a final piece of Graham's research, observations he made of the accumulation of organic material under over-mature conifers.

Its easy to get into the habit of dismissing exotic, coniferous plantations in Cymru and elsewhere as generally “bad things” in that they severely restrict or suppress native species. There's no real doubt about this, however, given that here we are surrounded by an exotic, coniferous plantation, its as well to have a good look at what there is as some of it is very interesting indeed.

The term over-mature is used in relation to commercial forestry where trees are generally harvested at around 30 or so years of age. Here in the “Core Block” of Coed Y Brenin, the oldest parts of the 19,000 acre plantation, many coupes or stands of conifers have been left to grow far beyond this commercial maturity, most notably the century old Douglas Fir to the south and many other stands are into there eighties now.

For example, almost bordering our own place is a stand of Scots pine planted in1942, one of the few evergreen, coniferous trees native to Britain. Apart from being beautiful trees, bark almost orange in the setting sun with trunks and branches that become more interestingly curved and bent as they mature, they don't form the same dense, closed canopies in the way many of the other, exotic conifers do. This means that the understory can be quite rich and varied and here includes birch, heather, bilberry, ferns and mosses.

Graham makes mention of a similar stand of over-mature conifers, planted in 1950 on a steep slope where the progressive rising and opening of the forest canopy as the trees age allows more light into the forest floor and promotes the growth of ground vegetation with mosses (polytrichum and plagiothecium) predominating plus ferns. What was particularly interesting about this study was Graham was able to make comparisons with two other sites on the same hillside, an area of sheep grazed pasture which had not been planted and hence acts as a control plot and an area of clear-felling.

Graham measured soil development beneath the grassland at a stable profile depth of around 90cm but under the conifers he found that the combined effects of trapping slope wash sediment and the addition of organic material over a 50 year period had led to the development of around 140cm of forest brown earth. He suggests that the limited depth in comparison to the conifer plantation may be due to less efficient trapping of downslope sediment wash by grasses and the accumulation of material from the understory. That's an addition 50cm of material under the trees.

With regard to the clear-felled area, he made the following observations:

“clear felling was accompanied by the die back of mosses and ferns through reduced humidity...Within one year of clear felling, severe erosion led to the removal of over a metre of forest brown earth to leave only 30cm of matted humus as a relatively impermeable hillslope cover above periglacial deposits”.

That is a huge amount of material sent off on its long journey downstream to the sea and really emphasises the importance of continuous cover in plantations, something that the British forest authorities (the Forestry Commissions in England and Scotland and Natural Resources Wales here is Cymru) still have not come to terms with. As I write this, NRW are clear-felling the top of Mynydd Penrhos.

I'll finish with a final quote from Graham:

"Mature conifer and broadleaf woodlands lying within the high rainfall zone are both able to develop the prolific moss and ground vegetation seen at Hermon [in Coed Y Brenin]. Moss growth maintains the humid conditions within the forest. Thus, the ecological system becomes self-sustaining and soil accumulation is promoted. Clear felling destabilises the moss-fern association, leading to soil erosion. The greatly altered nature of the hill surface produces a substantial increase in surface run-off during storm events”.

Many thanks for reading and a warm welcome to new subscribers. This piece is the last for now looking at forest hydrology. As always, comments, suggestions, requests, critiques etc. are most welcome.

Various pieces are coming your way in the near future. Delays recently have been due to a very intermittent internet connection (just come back on after two days without) and sloooow speed- currently 220Kbs, plus busy gardening time of year and still trying to finish firewood for next winter. Pah! Pathetic excuses!

Be prepared for more on the many species of Coed Y Brenin, plus internet and web site energy requirements (amazing how much carbon budget we users can tot up without really being aware of it) plus more of the Patafiction, Konsk together with chapter list and links for new subscribers and a justification for fiction as a means of passing on information. Wow, I am entering busy mode. Hwyl! Chris

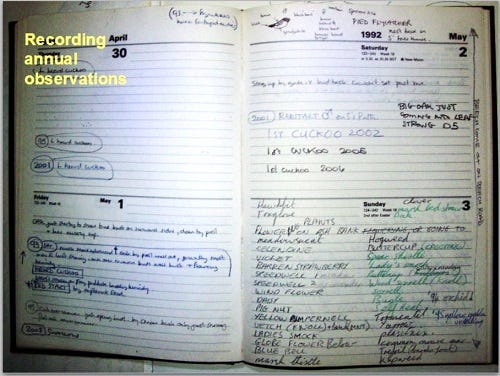

incidentally, we use an old diary to record the arrival or appearance of different species each year, such as swallows or the first cuckoo, simply writing the year and species on the appropriate date. This record has built up over nearly forty years and its fascinating to look back at the range of arrival dates over the decades and speculate on the reasons not only for the wide variation but also apparent favouritisms for certain dates.

above: old diary used to record annual appearances of various species, notably here, cuckoos and swallows but also a list of plants currently flowering.

Loyal subscriber Andrew commented, correctly, that what I had described as Graham's experiment was in fact a very large series of observations. An experiment is where we change an element in a system and then observe the consequences of that change. An experiment is usually designed to disprove a hypothesis or theory. Graham’s work is better described as a study. Thanks Andrew, point taken.

Links to Dr. Graham Hall’s work referenced in the three Forest Hydrology newsletters are given below. They make fascinating reading and contain many useful clues for permaculture designers and anyone interested in forestry and water management.

The role of forestry in flood management in a Welsh upland catchment

Mechanisms of flooding in the Mawddach catchment

An Integrated Meterological/Hydrological Model for the Mawddach Catchment North Wales