Facing up to Disaster(s).

And where that might take us.

I have been considering, with some reluctance, writing this piece for a while now and though I intended to post the next episode of Konsk, the Patafiction, this one kept getting in the way. So perhaps I need to get it out in the open to see it more clearly, for myself if no one else. I'd be very interested to hear any feedback.

Firstly, some background. As a ten year old in the mid-1960's I became interested in space flight and bought a book that my folks thought would be too advanced for me. It gave a detailed account of the history of rocket flight up to the then current US Saturn Five space missions that eventually got to the moon and included many photographs and diagrams. I gradually worked my way through it.

It began from the Nazi V1 and V2 rockets of World War Two, designed by Werner Von Braun. The first was just a self-propelled or flying bomb with no targeting capabilities- just point it in roughly in the right direction with enough fuel to get it over London, more or less and send it off. The V2 was much more like the guided missiles to come.

After the war all the main allies, the USA, Soviet Union (USSR) and the UK did their best to extract as many of the previously Nazi scientists who'd been involved in developing these weapons, for their own use. Von Braun ended up in the US and continued to design rockets that led to both the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) or Minutemen of the US primary nuclear "defence" system and the rockets like the Saturn Five launcher that took men to the moon in 1969.

As a ten year old the Saturn Five missions captivated me but I was aware that at the same time as the space race between the US and USSR was developing, so too was the nuclear arms race, both being intimately connected. So, for example, with nuclear weapons already numbered in the thousands on both sides, when the USSR developed Multiple Independently Targetable Re-entry Vehicles (or MIRV's), allowing the fitting of five or seven independent nuclear warheads in each of their existing launch vehicles, there was panic in the West and the rush to build more, bigger and better nuclear weapons. At secondary school, non of my friends wanted to talk about this because they found it so frightening to think about it.

For the latter part of the 1960's and throughout much of the 1970's the outbreak of a nuclear war seemed pretty inevitable to me. This wasn't helped by reading articles that suggested one could easily kick off by accident (indeed, we learned much later that this nearly happened on several occasions) . Also, despite the argument that a nuclear war would end in total destruction and hence anyone would be mad to start one (Mutually Assured Destruction, or MAD was the name given to this "policy") there was still the chance that one party might try getting in a First Strike, taking out sufficient of the enemy's defence and response systems to mean the first striker might survive1.

As we progressed through the 1970's I also became more aware of the increasing environmental damage due to exploitation of Earth resources and pollution plus a burgeoning global population with no sign of any slowing down.

My part in it all was made very apparent when in 1975, one of my biker friends, Tony, explained to me that the aerosol paint I was spraying on our friend Martin's BSA ZB32 motorcycle was causing a hole in the ozone layer. At first I didn't believe him as it seemed so impossible, that little me waving a spray can about could be part of such enormous damage. Later, I checked it out in my dad's New Scientist and, crap, he was right. That same day, Tony also went on to tell me about global warming being caused by burning fossil fuels but at the time the consequences of the damage was thought to be several centuries away. Still, it made me think, every time I filled the bike up at the local petrol station.

Whatever, to me, the environmental damage just seemed to be running completely out of control with no end in sight other than disaster. Successive governments in the UK seemed completely unaware or unprepared to do anything about this and were caught up in a range if issues that just seemed to get in the way of any real, valuable action. I began to think that there were other disasters looming as well.

By the end of the seventies I was more or less a nihilist, not believing in anything, least of all that anyone or any group was capable of getting us out of the trap I could see closing around us. I thought that money was completely involved in this and that, basically, the more money you had and spent, the more damage you did. My response was to become something of a survivalist, deliberately looking for somewhere out of the way to live and attempt to survive the chaos that felt inevitable.

Moving further north from Aberystwyth up to Dolgellau was part of this but it was here that something I'd already learned came to the fore. From the mid 1970's to the end of the decade I had become involved in Theatre, as a student first and then as a professional. Producing a performance for theatre is a completely co-operative venture, requiring the fusing of different strands of expertise (lighting, sound, set design, costume, acting, directing, publicity, administration etc. etc.) into a coherent whole, a hugely creative process that is totally dependent on a group action.

Although I considered many of the productions I worked on to be absolutely trivial, there were some that I felt had some real merit in terms of making an audience sit up and really think. Some of the experimental theatre produced by Cymric companies like Moving Being and Cardiff Laboratory Theatre, for example, as well as the small touring shows of Arad Goch (Red Plough) or Cymni Cyfir Tri (Count Three Company) and others were genuinely exciting, riveting and at times shocking experiences. Although you can show more spectacle through film or present a longer argument through a novel, there is something about the immediacy of a theatrical performance and the fact that another human being is "doing it", right in front of you, in the now, that gives it an impact that simply cannot be found in other media.

above: Cwmni Cyfri Tri production of Joli Boi, Directed by Jeremy Turner of Arad Goch, Set design Eryl Ellis, Penmachno, built by me.

So when I got to Dolgellau there were two very positive experiences that I had brought with me, the ability of a group of people working cooperatively to create something very powerful and the effect of live performance.

In Dolgellau my disillusion with the world was challenged immediately as we fell in with local people who often went out of their way to make us welcome and give us time and space. I remember after only six months, having been invited to one new friend's 40th birthday party that started with a band in a local pub, watching other folk arrive and counting the number I had met and felt I had had a significant, good conversation with and being amazed at reaching over 60!

During the next decade, the 1980's, this broad based, fluid, largely undefined bunch of locals came together at various times to work cooperatively on a variety of projects, initially under the leadership of Dave Reynolds who lived just down the road from us when we were village based. When I say Dave was the "leader", I would be better saying, Dave was someone who others were prepared to follow. On the surface a most unassuming and gentle man, he managed to inspire us to want to be involved, to want to take on a role without ever telling anyone to do anything. The results were very successful, completely unfunded projects that seemed to come out of nothing, such as a Green Gathering in Dolgellau, a Concert for Africa at the time of Live Aid and the establishment of the Mawddach Wholefood Coop which is still running today.

above: Green Gathering, Dolgellau 1984 (?)

The 1980's for me began with what were then seen as individual challenges, problems, threats, whatever and attempts to solve them, voiced and demonstrated by individuals within this fluid group, such as the War Against the Arms Trade, CND, food issues, Veganism, Feminism, domestic violence, lack of affordable housing, unemployment and on and on. Through many conversations that usually became deep, often challenging discussions, these began to come together and coalesce in some way. Then in 1989, just twenty miles up the road at Muriau Gwynion, I attended my first permaculture design course, facilitated by Eric Maddern and led by Andy Langford and it all seemed to come together.

With permaculture design it seemed that here was a strategy which could solve many of the current challenges at once, at a local level and also, as its influence expanded, turn things around at much larger scales, we could "save the world"! Oh, how naive, how innocently arrogant I was! No matter, to feel a hope like that and to share it with a cooperative group of like minded people, was too much to resist.

For the next few decades I immersed myself in permaculture design, through study, practise and teaching, meeting several thousands of people and working with and through the Permaculture Association Britain. Within this permaculture design bubble (though a large and diffuse collective, it was still a bubble) and its continuously positive attitude of "the problem is the solution", all seemed very rosy- very, very rosy.

Meanwhile however, on a personal level, I seemed to be experiencing disaster after disaster, repeated illnesses, largely Lyn's, including three different cancers, three separate emergency abdominal surgeries, my own go at Multiple Sclerosis, splitting up repeatedly then getting back together again, the rejection of our planning application for a permaculture holding, after twenty years of living on temporary permissions, being presented with eviction orders...

And also meanwhile, on a global level, despite the world's governments' and peoples' increased understanding of global warming and what was causing it, backed by continually growing amounts of evidence, generated by thousands of research scientists, though the IPCC and becoming ever more visible and tangible to many communities across the world, those CO2 emissions continued to rise, year after year and they still are. We could also throw into this pot the growing distractions from solving anything produced by multiple, highly destructive (of life and infrastructure) wars and the possibility of nuclear weapons being chucked into the mix at some point. It is not surprising then that ideas about impending disaster, nuclear war or collapse, whether financial, economic, environmental or societal, all of them in that order, or some of them, have made their way into the mainstream2.

Indeed, many folk I know talk about how after some sort of major disaster that tips current capitalist society over the edge and it all finally breaks down3, we will be able to recover and will have the chance to create genuinely sustainable societies. As the CO2 levels generated by capitalism gradually fall and the Earth starts to cool down, these new societies, operating at much lower energy levels, will be able to survive into the future.

However, this seems to me to be a highly unlikely scenario. Even if CO2 emissions could be stopped immediately (and we know they can't or won't be), the Earth will continue to heat up for many, many decades to come and we can already see what the current warming has done. So even given a massive change in consciousness, at both grass roots and at the top, things are going to get worse, and worse. And we don't know when, or even if, they will ever stop.

So if we accept all this, where does it leave us? Where do we go from here?

Here are some of my thoughts.

When I look back at my lengthening life experience, I see that I have oscillated between the belief in an inevitable impending doom and an opposing belief that it will be possible to sort everything, somehow.

Thinking about that personal oscillation between "We haven't a chance" and "Its all going to be fine", if I am completely honest, the real answer is that I simply don't know what is going to happen and I don't think anyone else does either, not for sure. So I have to accept the dynamic tension between those two opposites and the fact that the future is uncertain and is likely to remain so.

On a personal level, living in the now, in the moment, being grateful for each day as it dawns, is both a current and ancient solution to the traumas of human life. An awareness of the possible immanence of death is at the root of many spiritual traditions; we are all going to die anyway and we don't know when, so why not make the most of what we have?

I've also talked before (Ways to Wellbeing) about an integral approach, the foundation of which is looking after ourselves; after all, if we can't look after ourselves, how can we really help anyone or anything? So something along the lines of the physical, emotional, mental and intuitive practise.

I still think permaculture design is probably the best approach we currently have as to how we might live lightly on our planet, how we might create resilient local communities able to provide support for each other when disasters roll in. There are no reasons why these local interactions should not be enjoyable and fulfilling.

From my own experience of working with collaborative groups of like minded individuals, whether in theatre, community groups or permaculture design courses and actions, on projects which have genuine relevance and real value, such as local food security systems, can be immensely rewarding. In some ways, these collaborative groups are already the embryonic societies evolving towards a genuinely sustainable future.

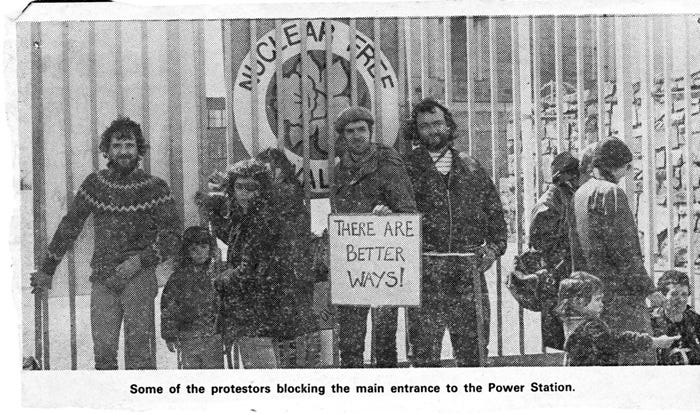

above: 1980’s, local protestors at the site of the Trawsfynydd Nuclear Power Station after it was kept running long after its planned closure date and cracks had been found in the cores. The two reactors are now shut down, part way through decommissioning and still highly radioactive. From Left, Dai, little Hannah, Annabel, me with the sign, Buff (rest in peace old friend) and I think the nipper lower right is a very young Luke.

But perhaps we should also be prepared to take much stronger actions in defence of our beliefs, or even in some form of confrontation with destructo-culture, though what form this might take is not clear to me. The actions taken by say Extinction Rebellion, while certainly attracting attention, often seem to soak up already stretched public resources and the ripples appear to die away very quickly. Perhaps the ability to take radical action increase as we age; in some ways, as I get older, despite now having a home and a lot of stuff, I somehow feel I have less to lose and so maybe I should be sticking my neck out much, much further.

We should also bear in mind that the unexpected does happen, out of the blue as it were. A significant example was the collapse of the USSR and the fall of the Berlin Wall, something that could not have been predicted even just a few years before it happened. Ultimately the future is unknown and there are bound to be many events that will take us completely by surprise and they need not all be bad.

That's it. I know I promised more Konsk last time but this piece seemed to have to get written. I would be very interested to hear any feedback you have. Next up will be Konsk, I hope... Thanks for reading. Hwyl! Chris.

Incidentally, it was thought that an ideal time for a USSR First Strike on the US would be Thanksgiving, when most of their armed forces were at home celebrating and a nuclear attack on the UK and Europe would be on Christmas Day, for similar reasons. When I learned about this, it did put a bit of a damper on several Christmas' for me until I got used to the idea and stopped worrying about it.

I have written about collapse in some detail on Substack here and here and you can find a useful piece by Misrule here.

Deep Adaptation takes a further last step and accepts that collapse is inevitable, will be total and permanent with no chance of recovery. Fronted by folk like Jem Bendall, it covers dealing with despair and suggests reason why and how to go on.

However, it should not be forgotten that capitalist society, even though founded on unsustainable beliefs and practices, is still a complex system and one thing we know about complex systems is that they continually reinvent themselves, like a continuously breaking wave that never actually breaks. In some ways I have been waiting for capitalism to break down for most of my adult life and it is still going.

Very interesting Chris, and very muc in line with my own life experience, the oscillation between we are totally screwed, to we really can fix this.. if only we put our minds to it. I think the Western world is now collapsing, imperialism is not sustainable, and that sudden and unexpected change may even come about sooner than we thought. Meanwhile, what else can we do but tend our gardens and send some love out into the world.

If you ask an anthropologist they'll tell you that every generation that ever lived thought they would be the last. This time, however, it just might be true. It's very difficult to see a soft landing here and the social tipping points will become critical before the climate ones do. Food inflation and climate-related migration are already happening and will accelerate over the coming decades whatever we do. These are the factors that fuel populist and far-right movements, isolationism and conflict. This will prevent us from dealing with the consequences of climate change rationally and indeed accelerate them. I don't think the entire race will die out but if you put the graph of human population increase next to a mirror - that might be the optimistic outcome. As to how we deal with this on a personal and societal level I have no idea.