Descent, Transition or Collapse, which is it to be?

Or all three and more, all at once...

Part One

I came across a book recently, translated from the French, Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens, How Everything Can Collapse, A manual for our times (Polity 2020). Its a subject I'm familiar with, for various reasons and before I talk about it, I'd like to go back a bit, to set the scene, as it were..

During the period from the end of the second World War in 1945 to the mid 1970's or so, the western democracies saw the greatest investment in public services that the world has ever seen, on a vast scale that is unlikely ever to be repeated.

In the UK this resulted in, among a great many other things, the National Health Service and the Emergency Services, the Welfare State, Nationalised Industries to provide affordable energy, water and transport for the populace, a massive building program including council houses (1.5 million in the first decade), public baths, libraries, arts centres, public spaces, funding for the arts through the Arts Council, investments in schools and universities with free education to degree level and beyond. I could go on but this will suffice.

As a student in Aberystwyth in the 1970s, pretty much at the peak of all this investment, I received nearly a full grant for living costs; my parents, both earning, were required, quite rightly, to top it up by about 10% which they did- many thanks! My education authority, Kirklees, paid not only the grant but also my fees and my accommodation for my first year, in a self catering hall of residence (many thanks to them also!).

The grant worked out at about £30 a week. I know! It sounds like nothing now but the previous year I had been working as a House Mother at a School for Maladjusted Children, (a job title and school description which beg another story in themselves! Think lowest rung of care work). I had been earning just over £40 a week in the job so £30 a week was pretty good! Out of this I had to buy my food, which came to about £20, leaving £5 a week for books and materials for my courses and another fiver for entertainment. Okay you young uns, it sounds like nothing but in those days a fiver could get you four or five books and the other fiver covered a couple of decent nights out in the Students Union (beer 17 pence a pint...).

I remember coming out of the bookshop in Aberystwyth, with a clutch of new books under my arm, thinking how fortunate and privileged, how downright lucky I was, to be living in such an amazing country as Great Britain. I finished University with a degree and no debts and walked straight into a job. So how the hell did we get from there to the shambles we are in today?

Those post war years, bolstered by the huge, low interest loans from the USA (the Marshall plan that funded the rebuilding of hundreds of bombed out European towns and cities and paved the way for economic re-development- I'm including the UK in Europe here!) was a time of sustained economic growth of a consistent 5% or so.

What did this mean? It meant that every year could be seen as better than the year before, with visible development taking place all around you, increasing opportunities for education and better jobs, specialisation, technological and scientific advances; it created a sense of progress, that things would always get better and that was the way of the world.

Basically, it fostered the illusion that economic growth could go on forever, a myth that has been perpetuated by successive governments and is still clung to today by our political leaders, despite all the evidence to the contrary.

What happened in the seventies to shake this illusion is still being argued over but here I'll just raise a few pointers. Crucially, the first major oil shocks occurred as the oil producing countries reduced production, forcing a jump in the price per barrel. Oil and energy in general, in a highly energy dependant society are so closely coupled to almost everything else in that system, that the repercussions roll out and bounce back from a host of often unexpected and ultimately unpredictable directions.

Among the repercussions were obvious ones, such as the rationing of petrol, a slowing of that economic growth to recession (instead of growing year on year, the economy begins to shrink), inflation, meaning price rises and the cost of living increases, so understandably there's a growing demand for wage rises to match the new prices and when the wage rises don't happen, strike action. The wage rises further inflation, more price rises, more strikes and round and round it goes. Does this start to sound somehow familiar?

During the seventies, Trade Unions, formed originally to ensure safe working practices and fair wages for workers, among many other things, had become large and powerful. Much of the Uk electricity supply came form coal fired power stations so the miners and power workers were in extremely strong positions, indeed, strong enough to in effect hold Governments to ransom through strike actions that could bring the country to a near standstill. In an attempt to sit out the strikes, governments reduced the working week and implemented power cuts but they often gave in to the demands or called a general election- let someone else try and sort it out! Inflation hit a peak of 25% in 1975 and interest rates climbed to 17%.

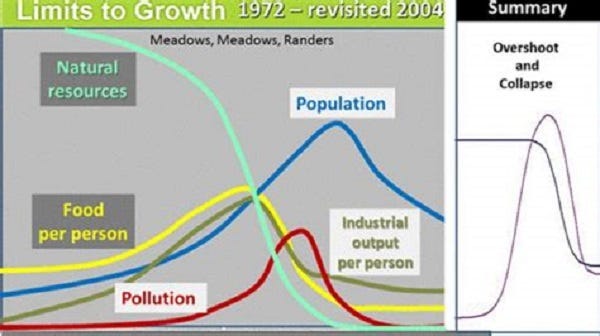

In 1972 Donella Meadows, Jorgen Randers and Dennis Meadows produced a report for the Club of Rome, a business group. Using a simple computer model that output various future scenarios they demonstrated quite clearly that continuous economic growth led, almost inevitably, to a systemic collapse in the 21st century. They've stuck at it and refined the model many times since then and still come up with the same result. Their book “Limits to Growth” marked the first coherent challenge to the myth of perpetual growth.

Towards the end of the seventies, after repeated governments and Labour, in particular, disastrously, had failed to come to agreement with the unions, with inflation effectively out of control, the threat of nuclear war there, always, ever present, it began to look to me and Lyn like its was all going to go down the pan.

I began to think like a survivalist (that's Prepper, young uns), drawing circles of exclusion zones on a map of Britain around towns, cities, military installations, industrial facilities, power plants and the like, trying to work out where the safe places might be in the event of a nuclear strike; there weren't any really, not here in Wales, anyway. Scotland looked about best but Lyn wanted to go back to Dolgellau, so that's where we ended up.

The immanence of economic collapse in Britain was postponed by the utterly ruthless actions of the Thatcher regime in the eighties. Put simply, destroy the power of the trade unions and sell the countries crown jewels, that is, sell the nationalised industries to private industry and the council houses to the folk who already lived in them (privatisation), invest the money in the city and turn a blind eye to a whole range of financial products based on the multiple sale of debt, so complicated that no one could really understand it or see where it might lead (deregulation); “The ethics of the city became virtually indistinguishable from those of organised crime.” (Tim Jackson: Post Growth- Life After Capitalism)

Turn your back on the idea of society and generate a new cult of the Individual; if you couldn't find work in your own community then “get on your bike” (Tebbit's phrase, I seem to remember) and look elsewhere, never mind the extended family and network of beneficial relationships (the community) that you left behind.

Moving to Dolgellau was good for us in that it brought us into contact with a friendly, supportive, community of folk who were more clued up as to what was going on, socially, politically and environmentally than anyone I'd met at university and, more to the point, were firmly rooted in the real world.

My concerns about collapse receded but remained there, in the background and permaculture design seemed to offer a way out of the mess. In permaculture design, we consider the existing state of a system, then imagine the ideal, future state we would like to get to and design the steps we need to take to get from the original state to the future state; we can call these steps the transition.

A young student called Rob Hopkins came to stay with us at our place and as part of his course, did an assignment assessing the role of permaculture design in fulfilling the UK governments commitments to biodiversity, using our place as one example. He was very inspired by Argel (the rough patch, re-vegetation project, rewilding whatever- see one of my previous articles for more details).

Of course, Rob went on to do some brilliant work, founding the transition movement which now has a global reach, providing towns and communities with the tools by which they could design their own transitions; the transition being, among other things, from a high energy, carbon based system to the zero carbon future. The presupposition being, of course, that the current state of the system is unsustainable.

Sometimes I think we've become so accustomed to thinking of our current society and economic model as unsustainable that we forget what that actually means- that is, if it continues as it is, it will inevitably break down at some point, it will collapse.

And next time I'll take this further and, eventually, get to How Everything Can Collapse, A manual for our times, the book that sparked this piece off in the first place! I know, maybe not as easy a read as some of the others but its important stuff and we need to get some sort of handle on all this because we are staring the harbingers in the face right now!

Thanks for reading and take care all- Life is still to be enjoyed. Hwyl!

And as always, please feel free to comment on this piece and help shape where the work is going. Many thanks.

Hi Jason, thanks for the comment. Yes, very familiar with David Fleming's work- I was asked to review his masterpiece, Lean Logic just after his death. Its an amzing piece of work and I would agree with you, still years ahead of its time. I'm glad you reminded me of him as I can add a reference to him in part two of Descent, Tranistion, Collapse. Thanks again. Chris

Are you familiar with David Fleming's work? https://www.flemingpolicycentre.org.uk/

It leaves me stunned, is based in very much the same question you ask, and I hear was one of Hopkins' big inspirations. It reads to me like it's still years ahead of its time, and he died more than a decade ago.