This piece has been delayed somewhat, due to me having to deal with my father's constipated house (at 95 he moved into a care home) and has resulted in my own home becoming somewhat constipated...my apologies.

In the last few pieces I've looked at possible fates of Coed Y Brenin. This time I want to begin to consider how we might avoid or at least lessen these potentially disastrous outcomes. First, I'll recap on the challenges.

Briefly, there is a bio-security issue centred around the very serious phytophthora diseases and in particular the susceptibility of Larch. Coed Y Brenin contains a lot of larch, scattered throughout the forest in stands of various sizes, some of which have succumbed to the disease and others that have been killed with poison, before they can catch it.

There is a considerable fuel load in the forest resulting from the Forestry Commission's “do nothing” approach, which has led to overstocked stands with dead, standing timber, large numbers of windblown trees that have not been cleared and old timber stacks. The poisoned larch, drying out while standing, adds to this fuel burden.

There is a major risk of wind throw in younger stands, up to 35 years old, again due to “do nothing” and failing to deal with extreme overstocking, hence the trees have very limited root space, making them prone to blowing over. This is worsened by the clearance of the dead larch continually opening up new faces to the wind. Additionally, there is the danger of wind-throw in the old (up to 100 years), beyond commercial maturity stands of trees as they reach the height limits that the landscape and climate can support, in particular, the thin, now alternately saturated or extremely dry soils and increasing likelihood of severe storms.

Rather than the piecemeal, one at a time approach of conventional thinking, from the perspective of permaculture design, we would attempt to create solutions that tackle several challenges at once, ideally all of them. Again, from that same perspective, rather than a single person or small clique working in isolation to come up with “the answer” and enacting it from the top down, we would rather work in open groups of either permaculture designers with practical knowledge of relevant subject areas (such as forest management, low impact building techniques, eco-village design, bio-remediation, community development and the like) or specialists in such fields who have knowledge of permaculture design. We would also want to make local people (like me!) the key part of this work, as ultimately we will enjoy or suffer the consequences of any actions. So we would want to develop solutions from the bottom up.

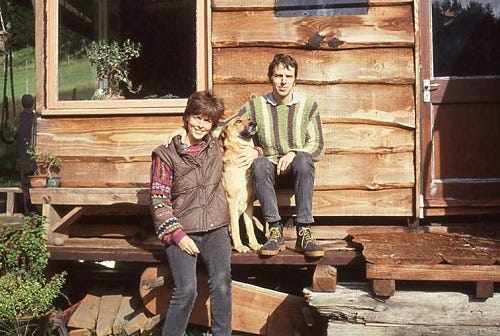

above: young low impacters…me and Lyn in 1992 in front of our first home-made house. Mainly Douglas Fir, material costs £800, built over three months by us. Over time it grew verandas and extensions and did us and our lad Sam proud for nearly twenty years. Genuinely affordable accomodation.

It is vital that any solutions to escaping the Three Fates, also address real, local needs and I'll emphasise the key ones here. There is a desperate need for genuinely affordable starter homes and decent jobs for young people who at present are forced to leave the area in search of work and accommodation. By genuinely affordable I mean sub £20,000 (or less, or otherwise affordable as in LETS or in “exchange for work” schemes or low rental properties with security etc.) and by decent work I mean work that is beneficial to the individual, the community and the environment.

above: low impact dwelling at Sych Pwll. Material costs £800 built by a small group in three months.

There is also a serious cost of living crisis as the current capitalist system of generating food and energy proves itself to be unaffordable to a growing majority of the population. So creating new communities (Cantrefi Newydd) based on locally generated renewable energies (wind, sun and water) and supporting the growth of home based food production and market gardens will be part of any solution. Thus, community engagement and involvement would be the first step towards generating an integrated solution.

In the 1990s I was asked by a group of woodland owners to run a permaculture design course specifically tailored to their interests and needs. So I hosted about twenty or so good folk who had woodlands ranging in size from a couple of acres up to a few dozen. As part of the course I got them to brainstorm possible forest products while I collated their suggestions on a blackboard with chalk, (I know, those were the days!). I struggled to keep up and after thirty minutes or so, drew the session to a close. I think they were as surprised as I was as we examined the list of over a hundred different potential products; and to think, Coed Y Brenin was planted just to produce wood...

On other permaculture design courses, I have asked student groups to come up with the material needs of human communities and again struggled to keep up as I collated their many suggestions. So what is the point here? Human communities have multiple physical needs and forests are capable of producing multiple yields; the two lists are almost identical. In short, the multiple yields of forest systems are a near perfect match for the multiple needs of human communities. That simple sentence is worth mulling over as it is the foundation for a regenerative future.

So who should really be managing our forests? It ought to be quite clear from the above that communities are best placed to manage, harvest and enjoy the multiple yields of forest systems. If we create clearings within forests and site dwellings and people within them, then we add intensive food gardening to the long list of benefits and provide homes and genuinely useful work for our young folk. This shift in thinking requires both support and education and is a genuinely regenerative, medium and long term solution.

above: local timber for our current home being stacked to air dry in about 2008. Mainly Douglas Fir, Cedar and Larch- basically “good wood”. The odd triangulated construction in the foreground is the base for the French trebuchet I built with my good friend Jim for use as a muck spreader, honest…what fun!

However, given that the current state of the forest is one of crisis (a word of Greek origin, meaning literally a pivot or turning point), there are some actions that require immediate attention and here, with a mind to raising some possibilities into more general attention, I will adopt the “When I am Emperor” approach, modelled at times by Bill Mollison, co-founder of permaculture design, who I was fortunate enough to meet when he ran an advanced design course in 1991.1

From a bio-security perspective, it seems bizarre to me that with something like phytophthora ramorum and pluvialis present in the forest, there are no warning signs on the many entrances and car parks. Given the large numbers of visitors each year, it is essential to make them aware of the risks of spreading these diseases. Where the disease is present, entrance to the public should be restricted.

Similarly, all forest entrance should once more display warning signs of the dangers of fire and penalties for lighting fires be re-introduced, as they once were, along with racks of beaters; on the spot intervention when a fire begins can be crucial to minimising the spread. In one of our local Community Council meetings, when we invited an NRW Operations Manager to attend so we could raise a number of questions, we were told that when the fire risk was high, warning signs would go up and barbecues would be banned but this is simply not good enough. Fire risk can be high at any time of year now because of lower humidity (drier winters and springs caused by global warming); in the last few years there have been forest fires in Scotland and Norway in the winter due to freeze drying of material.

above: Douglas fir trusses, purlins and rafters.

With regards to fire, it is vital that we reduce the fuel load in the forest and there are several ways we might do this. In the 1980s, I was very inspired hearing about the work of Jean Pain, a Frenchman employed to control undergrowth in a plantation. With a warmer, drier climate they were much more aware of the risks of fire and were aware that it was worth paying to keep the fuel burden in their forests low- this was far cheaper than dealing with a major fire and its aftermath.

Jean Pain harvested the undergrowth and chipped it. He fermented some of the chip with sugar in dozens of demijohns to produce wood alcohol then distilled the alcohol to make fuel for his chainsaws and other logging equipment, like his chipper and Matador, a heavy duty vehicle equipped with winches for hauling timber. So here there is both useful work (jobs) and product (income) and a move away from fossil fuel.

above: cedar (lightweight) plank wall, 300mm width allowing for plenty of insulation, framed with Douglas fir for additional strength.

Jean Pain also piled his wood chip into heaps, which heated up (like a compost heap) and by coiling large diameter piping through the heaps and into his workshop he effectively warmed the space during the winter. In true permaculture design style, these days we could stack in additional benefits here. Paul Stamets2, a permaculture designer who specialised in fungi and is now something of a global expert, advises inoculating the wood chip with fungi, easily done by breaking up inoculated fungal spawn and putting it through the chipper with the wood.

Fungal species would include those beneficial to the forest system, including species that will take up the niche that might otherwise be occupied by honey fungus, and also edible species, opening up opportunities for further employment. Thus we lay a foundation for healthy forest redevelopment, reduce the fuel burden, produce food and create employment, in the forest.

Several decades ago, the embryonic, forward looking Welsh Government supported the setting up of cooperative groups to trial alternative farm products, one of which was mushroom production; our hay man (Gwilym Gwair3), was part of the original cooperative group and now produces several hundred blocks of fungal spawn per week of a variety of edible species. So the knowledge and experience is already here.

above: Blue oyster mushrooms fruiting on a block from Balwd Ac Ati, a gift from Gwilym Gwair- thanks Gwil!

France provides other lessons in forest management that we would be well advised to consider as our climate continues to warm up due to global warming. I called in at the Forestry Commission's offices in Dolgellau in the mid 1980s, seeking support for our first planning application for a permaculture holding and met the then District Manager, Mark York, a military man, as were many at the time. Mark talked about visiting the French forests and being very impressed by their practice of continuous forest cover, not that we could do that here, he explained, the Commission being tied to the “clear-fell and replant” approach, though he couldn't say why this was so. I could, its basically capitalism; short rotation (30 years) forestry provides returns for investors within their lifetimes. A large number of people, including folk like Terry Wogan, benefited from this during the seventies and eighties as new plantations were rolled out over freshly drained peat bogs...

Mark York also told me how French farmers were subsidised not just to plant trees but also to manage them. On the very few occasions I have travelled abroad I was interested to see blocks of well spaced poplar with room to drive a tractor between them and harrow the ground to keep it clear of vegetation, hence minimising the fire risk. The poplars were high pruned (brashed) in order to produce tall, straight grained trunks of knot free wood. He went on to describe French hardwood plantations of high pruned oak with other tree species planted beneath.

above: larch flooring over Black Mountain’s sheep wool insulation.

Several decades later while working at the Signs Workshop in our parish, (one of the very few successful, forest spin-off businesses, more of which later) I came to appreciate that strategy. An order we got required straight grained, knot free oak posts, 5 metres in length and 150mm square section (that's about 15 feet long and 6 inches square). Timber of this quality is virtually impossible to source in the UK so we had to import it from France (and later from Germany). I had never seen anything like it and was boggled; it seemed a shame to be just using it for posts...I tried to imagine what a Coed Y Brenin of hardwoods would look like now if they'd planted oak a century ago, instead of Douglas Fir...The price of this kiln dried oak is about £2000 per cubic metre; Douglas Fir is less than £100 in the round....

Not that I would knock Douglas Fir, even relatively fast grown here in Coed Y Brenin, its an excellent structural timber. I built our first low impact dwelling from it and it was our family home for twenty years; we only took it down because we were presented with eviction orders from the Roman- sorry, I mean Snowdonia National Park (more on that at some point..). The roof timbers, joists and framing of our current home are all Douglas, along with cedar cladding and larch flooring, also from the forest, basically “good wood”.

above: cedar cladding over the plank walls. A remarkably stable wood liked by wasps- you can hear them rasping it in the summer.

So I'm going to leave you with a question which I think you will be able to work out- here it is: if you were going to plant 19,000 acres of trees, such as Coed Y Brenin, intended as productive forest, what is the single, biggest omission you could make?

Next time I'll provide two answers to that question and continue The Great Escape as we seek to avoid or at least lessen the threat of those looming Three Fates.

Many thanks for reading and please, leave some comments!

Thanks for this Chris. I too built a cheap house, mainly from Douglas Fir, that Faith and I still live in. We live near many trees, and for my woodturning I use chestnut, alder, ash, beech, oak and cherry all from within 500 yards of our house. Ecovillages in forests make total sense. We need thousands of them.

I'll keep my eye on this blog now that I found it. And it woul be great to catch up in person sometime as well!