Well, this has been a long time coming...circumstances seem to have conspired against me over the Solstice season in a number of ways including heavily overcast days and short day-length reducing solar power to practically zero, low temperatures (down to -5.2. Battery efficiency reduces with temperature, taking longer to charge), equipment failures, animals requiring veterinary treatment, family commitments and the like, among a number of other events, unforeseen and random.

Also, perhaps because this piece is a bit more personal than some of my other writing, I may have been reluctant to finish it off, as if it is not as worthy or something. I had intended to post it somewhere in the middle of the festive season as many of us are at home then and it deals with home and place. Anyway, here it is, with a warm welcome to new subscribers and old and here's hoping the year unfolds in at least some positive ways for all.

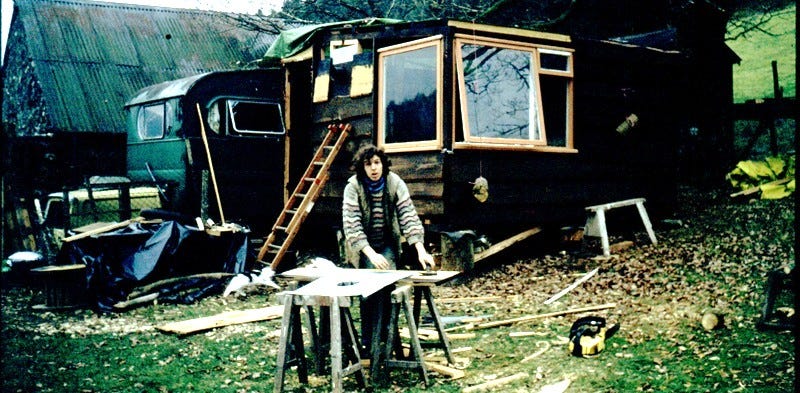

above: 1986. The patch of land that was to become our home, our place. North is to the right. The rough patch, or Argel, is towards the bottom left of the picture.

Way back in 1977, in Aberystwyth, my wife Lyn and I, in our early twenties, decided that Land was what we needed and that getting a piece of Land was more important and probably more achievable than getting a house. She used to buy the Farmers' Guardian once a week and trawl through the adverts for land, reading out the interesting ones, just to get an idea, of course; it seemed a long way off.

We'd moved out of a flat on the very edge of town and rented a house up above Llanilar, pretty isolated, a nice enough location with fine views to the east but the landscape, rolling hills, had never done anything to me, never really touched me in any way.

Moving up to Dolgellau, a number of things happened. At the time I only had a full motorbike licence and had been most surprised to find that this also entitled me to drive a three wheeler. I bought our first Reliant Robin van from a lad who drove it down to show me; although I was legally entitled to drive it, I couldn't give it a test run because I'd no idea how to drive it. I bought it anyway and before he went off to catch a bus I had to ask him to tell me which pedals were which. Over the next week I taught myself to drive, going up and down our track at first, then venturing out onto the lanes.

It was a rather simple vehicle, only having three switches on the dashboard, one for the lights, one for a heater and a third which didn't do anything1. In the early days, Lyn, sitting in the passenger seat, used to shout out as we nearly grazed parked cars or seemed to be going into the verge, regularly reminding me that I wasn't on a motorbike any more.

above: Son Sam as a young sprout and the original, much used (and abused) Reliant Robin Supervan III that I managed to keep going for ten years. A very useful beast- note the tow bar. The old Landrover was a friend’s MOT failure that got dumped at our place for a few years.

Anyway, having only a Reliant Robin, which is not what you would call a large vehicle, more like a small boat in some ways, it meant our move up north required multiple journeys of about an hour each way. I squeezed in two round trips a day for four or five days and this meant we moved the bulk of what we needed to begin with and the journeys gave me time to think. I thought primarily about what on earth I was doing, what was I getting myself into?

We were at the start of the eighties, the Thatcher government was in power and beginning to roll out the programme of Neo-Conservative policies (privatisation and deregulation) that were to prove so destructive to communities and set the country on course for disasters to come. Unemployment was going up as the nationalised industries moved in to private ownership and were “rationalised”, that is, ruthlessly thinned down to cores that could make bigger profits. I'd made myself voluntarily redundant, leaving a reasonably secure job as theatre technician/carpenter, though it was poorly paid for the unsociable hours it demanded.

I was going to a new and to me, unknown world, to take on the role of a house husband caring for our young son, Sam, then just over two years old, in our new home, just outside Dolgellau. This, a small cabin on what was rather bizarrely known as The Ponderosa Ranch was all we managed to find but would have to do to begin with while Lyn went back to work at the trekking centre that she'd visited since she was nine and gone on to work at before we'd met.

To me it all seemed a bit dodgy really, a leap into the unknown but it was oddly laden with coincidences. One example was that the last show I designed, built and produced at Theatre Y Werin, (the People's Theatre) was The Wizard of Oz and the cabin we moved into on the Ponderosa was called Kansas and looked not unlike the flying house I built for the show.

above: The Wizard of Oz, Theatre Y Werin, Aberystwyth, 1980 I think. Designed and built by me, directed by Richard Cheshire, music by Neil Brand now of Radio 4 fame. Dorothy’s Kansas house is not unlike our first home near Dolgellau, a cabin called Kansas, although ours didn’t fly.

More significantly, on those north bound trips to Dolgellau, I began to notice something. The landscape you get around Aberystwyth changes very little at first, just low, rolling hills, fields and the odd bits of woodland; it is much the same all the way to Machynlleth but then, differences begin to manifest themselves, hills rise up, rock appears at the surface, valleys deepen and dark forest plantations appear and it all becomes a bit more interesting.

It was on leaving Upper Corris though that I really started to feel something. Passing through that little village, the road continues to climb and then there's a level stretch and between the valley sides ahead, the south face of Cader Idris rises up. Here was another coincidence, for some years earlier, trawling through the index of an atlas, looking for names for mountains that I might use in a fantasy novel I was working on, I came across the name, liked it and used it2. There was yet another coincidence in that the flat we rented in Aberystwyth was in a house called Cader Idris.

above: Cader Idris, although this is the north face rather than the southern view that first hit me. At 2,930 feet (893 m) it is really a whole range, stretching for miles and is a most fine mountain indeed, dominating the Mawddach Estuary.

On each journey, as the mountain rose up before me, I began to realise the differences in the landscape and what they meant or did to me. Here, instead of the smooth, even green of Aberystwyth's low rolling hills, was an increasing complexity of colour and form, patches of darker brown rushes, grey stone outcrops, gorse, scrubby thorn, bracken showing the better soils; it all looked a lot more complex and, well, interesting. It reminded me of Cumberland, my mother's homeland but I felt it as well, inside my chest, like a fluttering, a sense of excitement. I liked this mountain, it boded well.

After a year or so and we moved from Kansas at the Ponderosa, to a rented cottage called Minafon (River’s Edge) in Llanelltyd, a small village about a mile or so from Dolgellau. The cottage backed onto marsh and from our bedroom window we looked out over the river Mawddach and beyond, the whole sweep of the Cader Idris mountain range was laid out before us. We were to spend ten years here.

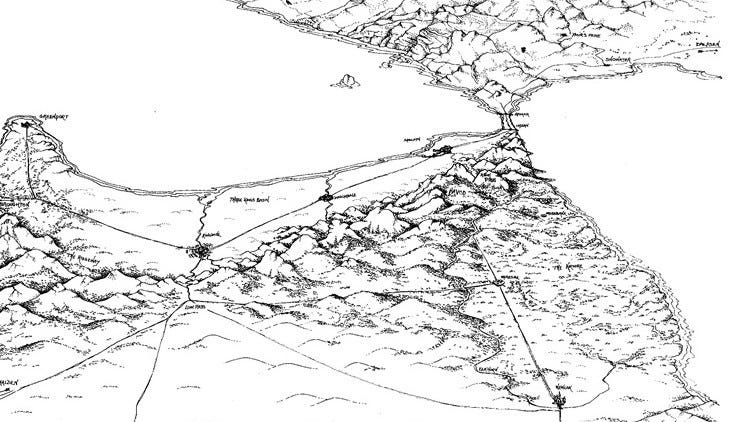

On trips back to Minafon from Dolgellau, the road crosses the Mawddach, still tidal here, some eight miles inland. On the bridge, my eyes would be drawn inexorably up the valley, to the northeast. Here, several ridges draw down together in some complex confluence, presenting perfect receding planes, each one slightly fainter and bluer than the one in front. More to the point, at this time every ridge and hill were wooded, layer upon layer of forest receding into the far distance; this was Coed Y Brenin, one of the Forestry Commission's oldest plantations. I liked it. It reminded me of the Canadian Rockies, only a bit smaller (a lot smaller).

Stranger still though, each time I crossed that bridge and looked north into the forest, a feeling began to grow inside me, that I would live up there someday. I couldn't explain this feeling, I didn't know where it came from or why it grew to feel so strong, so inevitable but I just knew I would live up there someday.

above: the view north to Coed Y Brenin and the confluence of the Mawddach with the Afon Wen (white or fair river) and the Afon Glas (blue river). Though this picture is taken not from Llanelltyd bridge but the old road running along the east side of the Mawddach.

During the time of Thatcher's Neo-Con regime the previously nationalised industries (coal, oil, power, water, communications, the rail network, council housing etc.) were sold off raising huge mounts of cash for the government3. Thatcher then turned her attention to the Forestry Commission with the intention of selling the national forests to private businesses but here she met with too much public opposition and was forced to give up the idea. Pity we couldn't have done more to save some of the others...

However, the various Forest Districts around the UK were encouraged to rationalise their investments and sell off bits and pieces where they thought they could. In Coed Y Brenin, as the forest was planted up, the better fields from the original smallholdings were retained, even after the farms themselves had been erased4. These scatter of fields, now become clearings dotted through the forest, had been retained as grazing for the horses who worked the woods in those early years before mechanised forestry supplanted them. Having lost even that purpose, the clearings were either more or less forgotten or rented to local farmers for grazing.

So from about 1980 onwards, these patches, ranging from five or so acres up to maybe twenty (about 2-8 hectares), were gradually put up for sale and the prices were not too high; could this be our chance to get some land? The first patch we saw, in 1982, was just over seven acres, surrounded by mature conifers, a small, sheltered, hanging valley, its lower end snipped off by a glacier. It was really nice, very varied in land form and soils from brown earth to peat, a stream running through it and several more feeding in from the eastern boundary, two boggy bits, a small, stone built barn with a tin roof and a few dozen mature trees including oak, hazel, willow and lime. We put in an offer of the asking price but someone had already bid more and we let it go, thinking it was just the first one, there would be more opportunities.

Over the next four years we looked at maybe a score of similar patches of land in or around Coed Y Brenin as they came up for sale. They were all good, interesting but somehow not as good or as interesting, as varied, as that first one we’d seen. Then Lyn’s boss at the trekking centre told her he’d heard someone was going to sell some land and that we should go and see him. So we did and as he began to tell us where this land was, we realised it was the piece we had first looked at four years previously, back in 1982. This time around we knew that it was the right piece for us- we scraped and borrowed the money and bought it.

above: our place in 1986. Scanned from an ancient, battered 35mm slide (young people, what we used before digital projectors and the pesky computers…). Sharp eyes will spot me centre right practising Tai Chi.

It took us another six years to learn enough about the planning system and gain sufficient support to get our first temporary permission to live on it in an old caravan and a relatively posh shed and we’ve been here ever since. Although having to commute about four miles from Minafon for those first six years was often frustrating and difficult at times, I came to see that period as hugely valuable. It forced an extended period of observation, experiencing the land in many different conditions. It became an absolute revelation and a delight for me to walk around what we called the rough patch5 every day, whatever the weasther, closely observing the natural re-vegetation that took place there, each spring welcoming young trees that gradually appeared, as if by magic, coming back into leaf.

Over the last nearly forty year, my relationship with this land has been amongst the most stable and reliable of my life. There have been times when things seemed utterly bleak (cancers, eviction orders, splitting up) and I have wandered down towards that rough patch weighed down with depression. Then by the time I had gone a dozen paces into it, I would find myself smiling, the depression forgotten.

above: me as a rather surprised and much younger looking low-impacter building the first dwelling at our place during the winter of 1991-92.

Once, after about fifteen years or so and towards dusk, I made my way into the rough patch by an unfamiliar route and found myself on the stream side in a circular hollow looking up at birch and willow pushing up a dozen feet above the shrub layer of gorse.

I didn’t recognise where I was! This is a wonderful experience to get on your own land. I deliberately suspended the moment, refusing to analyse my location and just observed the particular place I was in as if for the first time- it felt wonderful! After a while I began to imagine what it had been like when we first got the land, rolling back time in my mind to the rough grazing it had been originally. Then, remembering and visualising the appearance and flourishing of gorse, then the trees, protected from the browsing of deer, appearing above the spiky canopy and the gorse beginning to thin out in the increasing shade, up to that present day. I found I could reverse and replay the sequence repeatedly, looking in various directions, adjusting the visualisation to the unique topography, adding more detail as I did so. Since then I find I can now do something similar in any landscape, as though looking into possibly futures.

On courses and with visitors I would talk of our land as being my place but not my place, rather my place, as in, this is the place where I fit best. This arises from both adapting the land to fit us (growing gardens, building dwellings) and also adapting ourselves to fit the land (accepting limits to available energy and material sources, simplifying lifestyles).

After nearly forty years of interacting with this contained landscape, I can feel a very strong attachment to this, my place. I have been and still am reluctant to travel, preferring the stay-at-home culture that permaculture design implies but one reason is and has been, that I would rather be here than anywhere, really; this is where I feel most at home.

When I felt obliged to travel, to permaculture courses or convergences, I would say goodbye to the rough patch as I would say goodbye to Lyn. I would then just set off and practice "staying in the now" for the duration of the trip6, drawing my attention back to the present moment whenever I strayed into thinking about home.

One trip required five nights away (running a permaculture Tutor Training Course followed by the annual convergence) and was probably the longest time I had been away from home for twenty years. On the penultimate night, almost as an experiment, I allowed myself fifteen minutes to think about home and was nearly overwhelmed by the sense of deep longing that rose up, the feeling of missing my place. This feeling is Hiraeth in Cymraeg, a word that has no direct comparison in English. I allowed my self to feel this yearning for a while and then let it go and returned to the now.

Of course, I am also aware that such intense feelings indicate a profound attachment and such attachments, as with any relationship, are inevitably broken at some point, one way or another. In my imagination I can see many different ways that such an attachment could be broken and accept that at some point I will have to leave here, one way or another. Until then I feel a strong sense of privilege, that I found my place and am still here, at least for now. Whether this is down to Lyn, luck, fate, design or something else entirely, I really have no idea.

Thanks for reading. As always, comments are most welcome. Hopefully, with days lengthening and solar power coming back on line, slowly, I will have more opportunity. One intention for 2025 is to reinstate water power and I will no doubt document that here. Till next time, take care all. Hwyl! Chris.

In the early 1980’s, as a four year old, Sam used to watch Knight Rider, a TV series which featured a special car called Kit, that had a “Super Pursuit Mode”, which he mispronounced as super-per-soup-o. When engaged it gave Kit remarkable acceleration. One day we were driving along an empty Dolgellau bypass in the Reliant Robin and I casually informed him that our Reliant had super-per-soup-o. Meanwhile I’d slowed down gradually without him noticing. I told him it was only for occasional use and we had to make sure the road was clear, then, making it very obvious, I flicked the switch on the dashboard that didn’t do anything, floored the accelerator and we fairly hurtled onwards. He was well impressed! I managed to keep this mild con going for several years and on a clear road he would ask if we could use super-per-soup-o and I would oblige, having surreptitiously slowed down before flicking the switch and stomping on the accelerator- oh what fun!

the horrible irony of this was that we ordinary folk were encouraged to buy shares in industries that in many ways already belonged to us...Sure, many people were able to buy the council houses they lived in at often greatly reduced prices but they then became responsible for maintaining them themselves and the huge amounts of money made from the sales were not used to build more council houses, leading ultimately to the lack of affordable and social housing today.

I have described this process in some detail here on Substack in the section The Real Coed Y Brenin.

A fuller description of the rough patch or Argel and natural re-vegetation can be found here on Substack.

NLP practitioners refer to this as "staying in Uptime". It is also fundemental to many spiritual traditions and is perhaps particularly Taoist. I will talk about Taoism, The Way of Nature, at some point as it is probably the closest I have got to any form of religion or spirituality

Thank you for sharing Chris, such an enjoyable read. I do think that the little messages you receive throughout life's journey are guiding you to where you ultimately have a clearer sense of belonging, and perhaps being. Salamat Po!