The Real Coed Y Brenin

The Early Forestry Commission and the Erasure of Social History. Part One.

I've lived in the Dolgellau area for forty years now, picked up work in Coed Y Brenin from 1983, was fortunate enough to acquire land here in the forest in 1986 (thus becoming part of Thatchers Privatisation, story to follow) and have lived here with Lyn, my good wife since 1992.

Over that period and especially earlier on, I have taken pains to talk to the older folk whose memories stretched back to a time before tractors or cars, before mechanisation and farm amalgamation, when the bulk of the population lived in the countryside rather than the towns or villages. From them I learned an enormous amount and it is for them, as much as anyone, that I present the following piece, much of which is based upon what they told me. This forms part of a larger work, The Real Coed Y Brenin, which I will return to here, from time to time.

People may be aware of the rural villages and communities that were drowned in the construction of reservoirs to supply the growing need for water in the cities, many during the second half of the twentieth century. Not ten miles up the road from us is Llyn Celyn, constructed in the 1960s, under whose water lies Tryweryn, once home to a thriving rural community and still a core of Cymric anger.

This practice was not confined to Wales alone as drownings also occurred in England and Scotland, such as Derwent and Ashopton Villages under Ladybower Reservoir in Derbyshire, Mardale Green under Haweswater in the lake District, Green Booth under the reservoir of the same name in Lancashire, West End under Thruscross Reservoir, North Yorkshire and parts of the 15th century Longstone Manor under Burrator Reservoir on Dartmoor, Devon, to name only a few.

What is not so well known is that similar acts of erasure were performed upon other rural communities, under the auspices of the Forestry Commission. In the following I will outline the background to this largely unsung outrage.

After the First World War of1914-1918, Britain found itself practically stripped of trees, such had been the demand for timber during those terrible years of trench warfare. There was an element of panic and solutions were rapidly devised. The Forestry Commission was established with a remit to create and safeguard Britain's timber reserves through the rolling out of substantial plantation in various parts of the country.

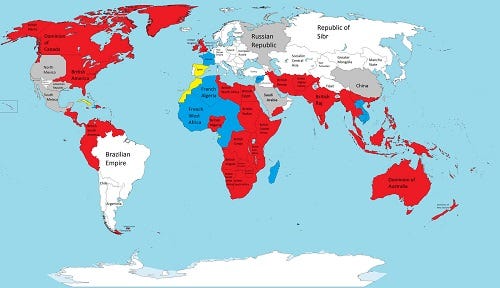

It was a time when Britain was still an Empire, nearly a third of the world was coloured red in every school atlas (it still was in the early 60s when I was at primary school, a tribute rather to the backward nature of our village school at the time and, to an extent, of the society, rather than to the reality to that vast and oppressive Empire).

Wales, Scotland and Ireland were referred to as The Provinces, to be exploited for their natural resources, in the same way as the further flung provinces of the Empire. In Wales this included the exploitation of people and had begun with a growing urbanisation during the nineteenth century; indeed, Wales was the first country in Europe where the urban population outnumbered the rural, occurring towards the end of the nineteenth century.

The exodus of folk from the land to the coal, iron and steel works of South Wales that fuelled the industrial revolution, was driven by extreme poverty deriving from successive agricultural depressions in the eighteen hundreds, the greed of landowners pushing up rents, the church's demand for the tithe (a tenth of all produce) and the English.

Following the ending of the First World War in 1918, the early Forestry Commission appointed officers to travel the country, liaising with the major landowners, both the old aristocracy and the new, made up of rich industrialists and businessmen who had often bought up the estates of bankrupt aristocrats. Those without heirs were particularly sought after and were persuaded to leave large tracts of land to the Forestry Commission (in other words, the Crown) in their wills, usually on 999 year leases.

The rural populations were told that the plantations to come would provide work for their sons and grandsons, forever, (A similar tactic appeared much later, when the people of Trawsfynydd were informed that a nuclear reactor was to be built in their parish. They were also told, informally, that the electricity generated would be so cheap it would not need to be metered).

In such a manner was the foundation of Coed Y Brenin, in the early 1920s, when several thousand acres of land were transferred to the Forestry Commission from the Dolmelynllyn estate for the establishment of a plantation to safeguard the nation's timber reserves. It was known first as Vaughn's Wood, the Vaughn's being the family who had bought up Nannau, the other major estate in the area, in Llanfachreth.

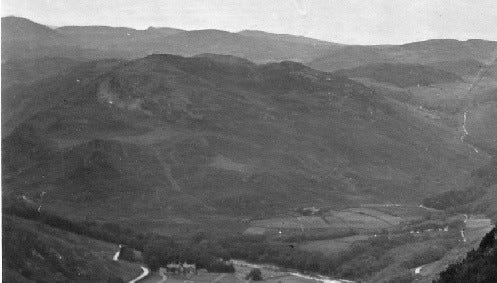

above: Mynydd Penrhos, before the Plantantation.

Here I am going to concentrate on the area known as Mynydd Penrhos and the community that originally lived there. Mynydd Penrhos is a great bulk of rock rising between the Afon Mawddach and the Afon Wen, much riven by faults and eroded into a complex landscape of crags, steep-sided hills, hidden valleys, shelves and hollows, thin skins of forest brown earth deepening in depressions or blackening to peat and bog. As with the much larger areas of land that would become Coed Y Brenin, it included many tenant farms and families.

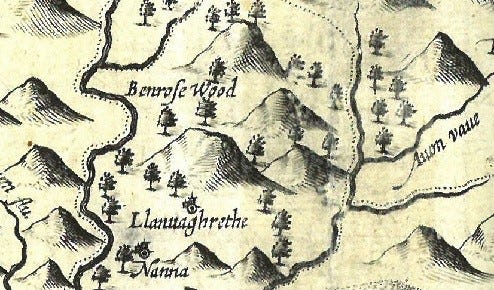

Up until the late 1500s, Mynydd Penrhos had been oak forest, marked on the few very early maps as Penrhos Wood or Penrhos Forest. The oaks were felled from the 1590s on the orders of Huw Nanney of the Nannau Estate in order to make charcoal for an iron works to be located near Ganllwyd in a money making scheme. Unfortunately for Huw it turned out that the Crown owned the forest and he was hauled up before the highest court in England, the Star Chamber and sentenced to imprisonment in the Tower of London. (This in itself is quite a story which I will look at in another part of The Real Coed Y Brenin).

above: map showing Mynydd Penrhos as Benrose wood.

Contemporary accounts mention that a number of poor families who had been living in the fringes of the forest, basically squatting, lost their homes when the trees were felled. This gives us some clues as to what occurred later, for from the 1600s on, maps describe Mynydd Penrhos as Penrhos Common. It seems that over the next few centuries, poor, landless families began to move onto the common and build very crude dwellings known as hofeldai in Cymraeg, or hovels in English. These families were basically squatters, with no legal rights of occupation, although there was a common belief in the Ty Unnos.

The Ty Unnos or One Night House, centred around the belief that if a dwelling could be built in a single night, it gained legal security, though there is no actual grounding for this in law. The Ty Unos was necessarily an extremely simple, crude dwelling, a hovel, usually built by the one family, although there are examples in some parts of Cymru of more elaborate, well planned structures constructed by well organised groups of folk.

More generally and more likely on Mynydd Penrhos, these hofeldai would be small, tiny we would say, consisting of two simple, gables of stone joined by low walls which might only be a foot or so in height (30-60cms); indeed sometimes there would be no wall at all and the roof came down to the ground. The roofs could be incredibly crude with all manner and shapes of branches laid together, covered in anything from gorse to heather, rushes and occasionally turf.

A fire for warmth and cooking would be made on a central hearth burning peat, for there was no chimney, the smoke simply being allowed to escape through the inevitable holes in the roof. They were described in contemporary accounts as rude dwellings, smoky and draughty that leaked when it rained. Yet these simple dwellings were obviously homes to families who began to garden and farm scraps of land that lay around them, slowly clearing stone from the ground to build the walls that delineated the first rough fields.

above: ruin on Moel Friog, on the eastern side of Mynydd Penrhos.

At some point during the seventeenth or eighteenth century, Penrhos Common became incorporated into the Dolmelynllyn Estate through the Enclosures Act- basically an Act of Parliament that allowed wealthy landowners (and all MPs at the time had to be landowners) to grab what had been common land for knock-down prices. As with other estates where squatting had occurred, the new landowners began to formalise the relationship with the squatters in order to be able to charge rents.

Gradually, stone barns appeared, usually attached to the early hofeldai. These could be well built and were probably funded by the estate owners, allowing for storage of hay and the sheltering of livestock, thus increasing the productivity of the holding and again, providing a reason to charge or increase rents. As these farms developed, some grew additional structures such as pig sties and other outhouses and more favoured ones, what we would call actual farm houses, the original hovels being allowed to go to ruin or sometimes being dismantled, the materials reused elsewhere.

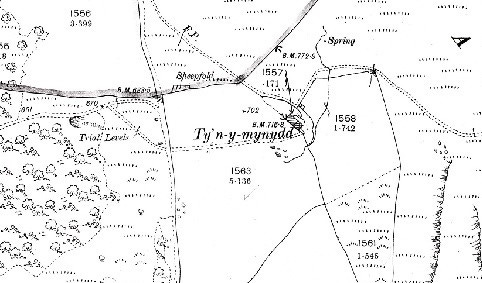

above: map from before the plantation showing a tyddyn, Ty’n y mynydd.

These were the tyddynwyr, or smallholders, who I have mentioned in previous pieces, and along with the cottagers, smallholders, crofters and others formed the bulk of the rural communities throughout Britain. On Mynydd Penrhos itself, several score of folk lived in a dozen or so dwellings in a scattered community closely tied with Ganllwyd to the west, Llanfachreth to the east (for the weekly markets held in both parishes) and Hermon to the north.

above: Ty’n y Mynydd as it is today…

Their farms were small, with only five to ten acres of actual fields. The walls enclosing the fields were built from stone cleared from the land. Indeed, stone clearance became a part of the rental agreements, so many hours being required for the work per week, a task usually undertaken by the women and children. As well as the walls, the land is peppered with stone clearance cairns, some of considerable size, an indication of the original landscape, strewn as it would have been with rocks and stones, tumbled from crags and left by retreating glaciers, including large erratics (boulders).

above: stone clearance cairn harbouring oak within the plantation.

There are also peat drying mounds, rectangular heaps of larger stones, with the long side angled to catch the sun, on which the cut peat was laid for a season before being brought in to barns for a further season of drying and only then being burnt to warm the houses.

At the time, stone clearance was one of the few land improvements the landlord could impose on the tenants of Mynydd Penrhos; rising on the boundary between lowland and upland, it was reached only by footpaths and one poor, long, uphill track, in places very steep, so the cost of hauling lime from the estuary, where the tall ships brought it in as ballast, would have been prohibitive.

With only a few acres of actual fields, the tyddynwyr depending upon more extensive, wilder grazing and each farm had access to additional land of various types which by usage became traditional rights. Each of these land types offered varied opportunities and are worth treating individually and I'll look at those in some detail next time as they provide us with useful clues for future designs. I’ll also describe what happened to all those families of tyddynwyr, as the Forestry Commission’s new plantation gradually encroached upon their holdings.

Till then, many thanks for reading. I hope you enjoyed the Solstice (the only event actually rooted in reality!) and the beginning of the return of the sun. For now, happy Christmas and take care, all. Hwyl!

As always, please feel free to comment on this and other pieces! Many thanks.

Chris.

This a wonderful historical piece. It demonstrates how much we can learn from a historical perspective. We usually do not know the consequences of such natural annnd beauriful environment being destroyed. The sad side of it is that unfortunetely we continue to do it in "modern times." No end to the destruction of nature! We have to intentionally act to stop these acts of violence against nature, Thank you Chris for enlightening me with such dertailed historical narrative. There is much to learn from history so we do not repeat the same mistakes in the name of progress. Francisco Perez

fascinating, thanks Chris. Reminds me of the book my mum wrote (The Wild Sky & others) about the Vaughn's and the Wynn's of Maes-y-Neuadd at Talsarnau, up behind Harlech. The oaks there were cleared for the armada, apparently....