Y Cantrefi Newydd part three

Cantrefi Economics: Boon Days, Favours and the Gift Economy

I'm going to move about here quite radically in terms of time and space and the connections may not appear obvious at first so, please bear with me. Hopefully you will see that it all makes a sort of sense in the end!

In the past I had thought that a Local Exchange trading System or LETS1, local to an individual Cantref, would be useful. There are various types of ongoing work that a Cantref will require, including infrastructure maintenance, such as the upkeep of the track and path network, water management, the repair of community buildings and services, perhaps management of a laundrette, library or IT hub and the like. There may also be community food gardens, orchards, forests and shelterbelts which require regular attention. I imagined that community members who carried out these maintenance and service tasks could be “paid” in the local LETS currency.

In turn, members might use the local currency to “buy” the services they use, such as net access, water supply, electricity, depending upon how independent each individual hearth or home, was to be. The LETS currency might also be used to purchase your plot in the Cantref in the first place and then paid back over time or, depending upon the way the Cantref chose to establish itself, perhaps purchase the security to live there, or a lease, the Cantref itself maintaining ownership of the land.

However, I reminded myself, some time ago, that LETS is just one option that Cantrefi might use and in itself is quite limited. True, the actual currency is only of any value in it's local Cantref and cannot be “spent” anywhere else; this has the advantage of keeping the currency circulating within the community but in some ways it simply replicates the cash economy at a (very)local level. So what other alternatives might we consider?

From my basic knowledge of history and prehistory, its obvious that there was a time when money, as we know it, did not exist. I often try to imagine what that was like and how folk had managed. Books and some anthropologists will say “barter” but then there's a rather embarrassed pause. Why? Because there is almost no evidence for this in the historical or archaeological record. That's not to say that it didn't happen but we need to think more broadly to imagine an alternative.

If we go back to our hunter/gatherer2 times it is pretty clear that we didn't need anything like money or barter, as everything that we needed was all around us, in our environment.

In Stone Age Economics3 there's a great account of a tribe living in small, semi nomadic bands. One of the men, Marshal relates, was particularly good at making flint arrowheads and so was pestered by several other men to make some for them. Although he'd promised he would, his main pursuit, as with many of the peoples described in this excellent book, seems to have been to sit around the fire, apparently doing very little, or wander about with no real goal in mind, pottering.

Eventually they collar him (not an appropriate phrase as, obviously, collars had not been invented) and get him to make them some arrowheads. That's it. There's no exchange, no barter, certainly no coin to change hands- he just makes the arrowheads for them, because he's good at it and they would like some. No doubt he does gain some sort of kudos for this action and his reputation within the group is enhanced, although whether he would consider this a good thing or not is not clear- perhaps he would prefer it if some of the other men got better at making arrowheads so he doesn't have to...

To give one further example from the book, several tribal groups live largely hunter/gatherer lifestyles but also have small, family, garden plots where they cultivate some food, largely yams. The different gardeners put in different amounts of effort into this cultivation, with some families producing considerable surpluses and others not even producing enough to feed themselves during the hungry gaps. When the cultivated food runs out for these families, they simply join another family who have a surplus and are fed from that. Again, there is no exchange of any sort and certainly, no value judgement is made as to the family being scroungers or anything like that; it is just accepted as the “way things are”.4

I have referred to the traditional local communities around me previously5, each one in their own unique landscape, largely self reliant in a pre-carbon society that is still, just, within living memory. Here, I want to jump back to a previous time and describe the Greek Polis, before returning to these traditional, local communities, as I consider both have useful clues as to how the future Cantrefi might be organised.

Back in the day, one of my Classical Studies lecturers explained that Aristotle's famous aphorism “Man is a Political Animal” is a gross mistranslation of the original Greek. He provided a much more literal and accurate version, as follows:

“Man is an animal whose nature it is to live in a Polis.”

For a start this headlines the classical Greek attitude that women were of less importance than men (in the early democracies, it was only the male citizens who had the vote) but it also begs the question, what is a Polis?

Again, the accepted translation of Polis (from which we get words like politics, metropolis and the like) as “City-State” gives a very poor, partial view of the original, and is largely skewed by our contemporary understanding of what makes a city.

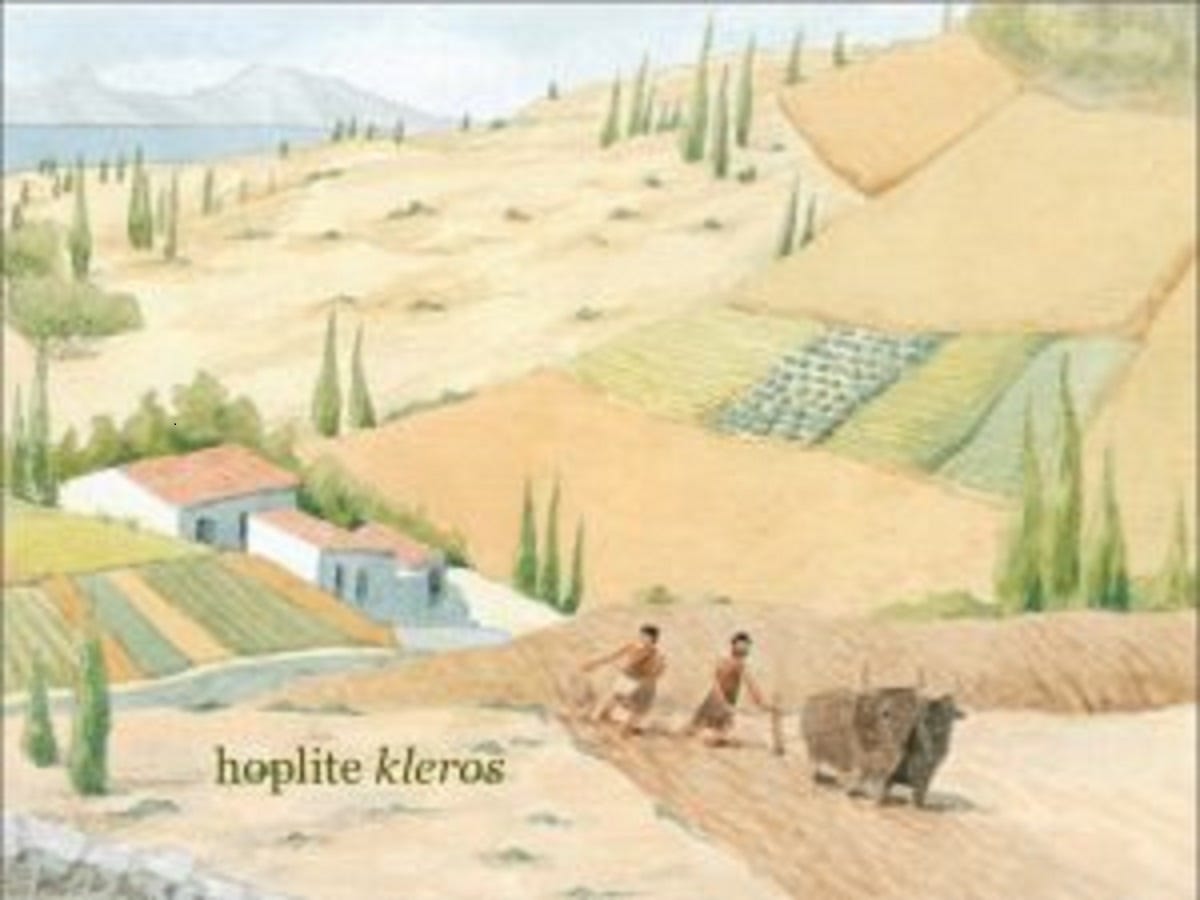

above: the Polis: not just a collection of dwellings.

In Greece, the scalloped edges of the Peloponnese create a series of distinct bio-regions separated by hills and mountains, allowing for the development of localised social systems, all based, at least initially, on farming. These units, comprising several hundreds, were small by today's standards, (one mentioned by Thucydides6 had only 75 voting citizens) and even at the height of its power, Athens, as leader of the Delian League, is thought to only have had about 24,000 voting citizens, that is, men...7

The Polis was not just the collection of dwellings where the bulk of the population of each bio-region lived ( the “city”) but something much larger and more inclusive, referencing the close community of people who lived there, the unique, defined landscape that was considered to go with the dwellings and the people, the particular religious beliefs and rites of their locality and extending backwards in time to include the traditions, history and mythology of the place and the people. In other words, incorporating the three primary perspectives in an integrated whole.

Now consider the traditional communities that abounded in Britain, not just here in Wales; these were subsistence, farming communities, where the bulk of the population lived, each rooted in their own unique landscape, with their own histories and mythologies (folk stories and the like), each with their own unique identity, with their own dialect and often their own words.8

I have outlined in other pieces here on Substack the way the a traditional community was thoroughly interconnected through such things as work, religious practice, celebrations, annual cycles and the like, plus the importance of marriages, births and deaths as times where folk are drawn together.

What is important to remember is that these traditional communities were largely cashless societies. Cash was only required for very specific purposes, one of which might be the payment of the annual rent to the Estate (which usual owned the land and properties), although here in Old Meirionydd, the House of Nannau would often accept rent in goods or services. The traditional way of acquiring cash for the rent was to take on two weaner pigs in the spring and rear them during the year. One was salted as meat for the family through the winter and the other was sold to pay the rent.

The other need for cash was for items that could not be produced locally, such as sugar (needed for preserving fruits, for example), salt (again, for preserving) and luxuries like tea.

above: the narrow, steep sided valleys of South Gwynedd led to distinctly local communities in the past.

Other goods and services were acquired without the use of cash. So, for example, a particular tyddyn (cottage/small holding) might have rights by tradition to collect fallen wood (windfalls) from a particular wood. There is an example of a woman in Llanfachreth whose tyddyn had the right to collect wool from certain fields when sheep start to loose bits of their wool prior to shearing, leaving the bits of fleece caught up in hedges or just on the ground. She gathered this, spun it, knitted stockings and sold the stockings for some cash.

above: Llanfachreth, occupying a prime location, a south facing slope on a plateau, sheltered by hills and the ancient, volcanic Rhobell Fawr and Rhobell Fach to the north.

With regard to services, such as shearing, for example, which required the help of a large number of people of different skill sets (gatherers, shearers, wrappers, cooks etc.), folk would gather at each farm in turn, usually ordered according to elevation, the lower, warmer farms, requiring shearing first. My Cumbrian grandfather, a subsistence farmer himself, spoke of these days as “Boon Days”, that is, a timely blessing or benefit, a day of doing favours.

The way the traditional communities operated and survived for so long is a big, rich subject and I have only given the briefest outline here. At some point I will describe how it was the change from a largely cash-less society to a largely cash-driven society that has proved the greatest threat to these communities and caused the greatest erosion, something which I would hope the Cantrefi Newydd of the future might hope to redress, drawing on clues from our history and pre-history.

While LETS can provide an easy to understand alternative to cash and capitalism, the idea of exchanging favours is something that is strongly rooted in the British tradition, but the economics of hunter/gatherers, best described as a Gift Economy, with no thought of an exchange, provides the most radical foundation for the New Cantrefi.

This way of being is already here in many ways and examples only need to be recognised and pointed out. It is inherent in permaculture design's ethics, the other half of “Set Limits to Consumption” being “Give Away Surplus” and is exemplified in the work of my friend and colleague, Frank, who is part of the Welhealth Cooperative, here in Wales.9

Till next time, thanks for reading. Please feel free to comment to help steer the ship and avoid the rocks. Hwyl!

Hunter/Gatherer is not a great term- my good friend Steven Read suggests “scavenger” to be more appropriate, the etymology being to examine or scrutinise, as in “what use could I make of this, I wonder?”

Marshal Sahlins, Stone Age Economics, Tavistock Publications 1974

This is still a great read, not least because it compiles various accounts of early anthropologists' attempts to record the activities of hunter/gatherer societies, divided in terms of work and leisure. This is often hilarious and pretty futile as, for example, they have to put fishing down as work.

There are two excellent Radio 4 Food Programmes on the Hadza people, who have lived close to the Rift Valley in East Africa for at least 40,000 years and still follow a hunter/gatherer lifestyle. A truly egalitarian society who share everything, eating from a menu of over 800 different species of plant, mammal, bird, insect etc. etc. they have the most complex gut microbiomes of any humans so far found on our planet. The second programme concentrates on this remarkable fact.

I’ve given links to the BBC website for you to have a listen to the programmes below:

Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War is regarded as the first real book of history. It is a remarkable account of the dreadful conflict that caused immense and lasting damage to the whole of the Greek world and beyond. You can get a free copy from Project Guttenburg

Its worth remembering that these examples of early democracies, such as Athens, were extremely limited; women did not have the vote, nor did the Athenians' slaves, who were thought to outnumber citizens by about three to one. Its also worth pointing out that many of those early democrats would have been horrified at the size of Athens, considering it to be much too large to be an effective democracy. In fact, as leader of the Delian League during the time of the terrible war with Sparta, Athens acted in a most imperialistic manner, enforcing membership of its league with extreme violence. Those same democrats would be even more horrified by the size of our democracies today...

Without going into too much detail, the citizens, originally farmers, preferred to live centrally and walk to their fields to work each day. The generally good weather in Greece meant that gatherings of the entire population of a bio-region could be held outside and the increasing use of slaves meant that the voting citizens had plenty of time to hang around in the Agora (the open area, or market place) and discuss politics. I’m NOT suggesting that the new Cantrefi should have slaves! However, an Assembly of the entire population, including the children, should be seen as essential.

Nesta, who was largely responsible for teaching me Cymraeg and firing my interest in the culture, explained, with examples, the differences in the dialects of Dolgellau and Llanelltyd (two miles apart), Ganllwyd (three miles from Llanelltyd) and Llanfachreth (two miles from Ganllwyd).