I posted some details of my 2024 rainfall records for the early part of the year, here on Substack and now have the complete record for the year. Interestingly (in the Chinese sense...) 2024 turned out to be opposite to what I had expected. I've talked here before about the dangers of looking for trends in weather patterns and expecting them to continue- they don't. So the previous few years here of cold but dry springs, warm to hot and dry early summers with falling humidity and increasing fire risk, followed by wet autumns was almost completely reversed in 2024

So we had a warm but wet spring1 followed by an often overcast summer with reduced but regular rainfall, no really high temperatures but high humidity throughout and a very overcast early autumn, well down on heat and light units.

Among other things this meant that successive sowing of broad beans, a completely reliably crop here for at least the last twenty years, failed totally, going mouldy in the ground. Summer growth was very slow and autumn growth non-existent, meaning many of my onions rotted before they were ready to harvest and the coloured sweet corn failed to ripen, again, both generally very reliable crops here. On the other hand, perennials, bush and tree species took advantage of the light but regular rainfall to put on considerable growth, along with all the less useful stuff (weeds...).

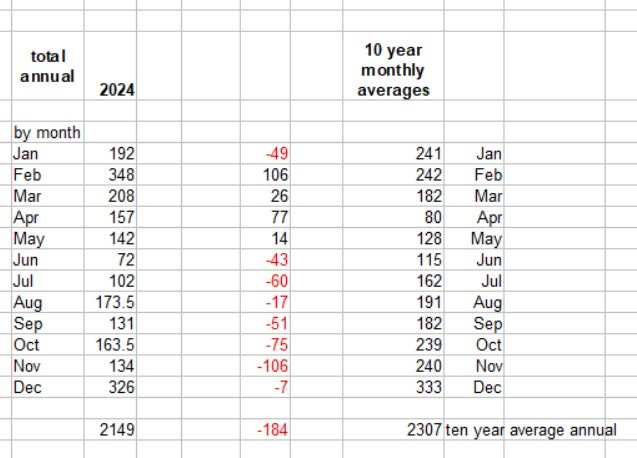

above: on the left, 2024 monthly rainfall figures here at Tir Penrhos Isaf compared to ten year average figures on the right and the differences in the centre. Red figures show the reduction in rainfall.

The figures show that from June onwards, every month fell short of the 10 year averages leading to a much reduced annual total. However, at 2.149 metres this still lies close to the middle of the ten year average. Annual rainfall here shows considerable variation from lowest of 1.682 metres in 2013 and 2022 to highs of 2.715 metres in 2017.

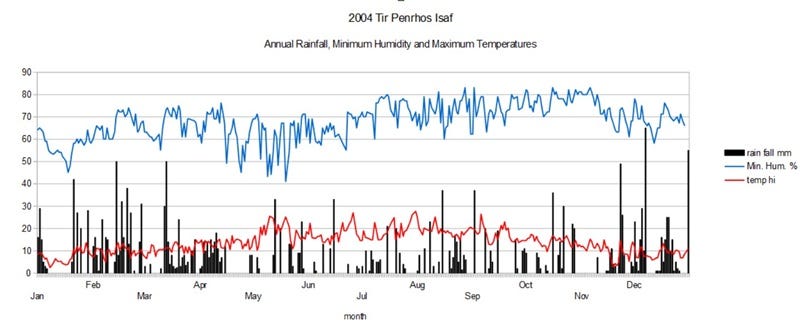

above: chart showing daily rainfall in mm (black bars), humidity as a % and minimum temperature in degrees Centigrade.

This show a few periods of more sustained rainfall, particularly early in the year, followed by occasional heavy bursts and numerous periods without any rain, the longest being 13 days (very unusual for us!). However, the temperature did not climb much above 25ºC and even in these dry spells the humidity hardly fell at all, remaining high throughout the year. Great for mosses, lichens and liverworts, slugs, moulds etc. and not quite so good for organic vegetables...It also meant that the fire risk was very low thorughout the year, phew!

This quite extreme variability in terms of annual rainfall (up to 1 metre) and variation in daily humidity and temperature is because we are looking at weather rather than climate. The latter, shows a disappointing (disturbing) lack of variation with overall annual global temperatures continuing the seemingly inexorable rise.

The recent visit by Storm Eowyn produced some interesting mixed comments from weather forecasters and other experts. Eowyn was touted on a variety of media, including BBC's Radio 4, as a "Generational Storm" or a "Once in a Generation Event". This surprised me for several reasons.

Firstly, the BBC journalist quoted the Shipping Forecast2's area forecast for Cromarty as an example of the extreme nature of Eowyn as Violent Storm Force 11 and this is indeed a severe storm, with wind speeds recorded at over 100mph. Yet back in the winter of 2013-14, as a succession of storms battered many different parts of Britain, the Shipping Forecast regularly gave out a plethora of Storm Force 10, Violent Storm Force 11 and even Hurricane Force 12 warnings, the first I remember hearing of in British waters (though that is not to say they hadn't been issued before).

Lyn and I would listen with some trepidation as the announcer read through the forecast, working their way around the coast and would be relieved to hear our area, the Irish Sea, as"just" Storm Force 10 or even Violent Storm Force 11 when the areas around us would be one worse, at Violent Storm Force 11 or Hurricane Force 12.

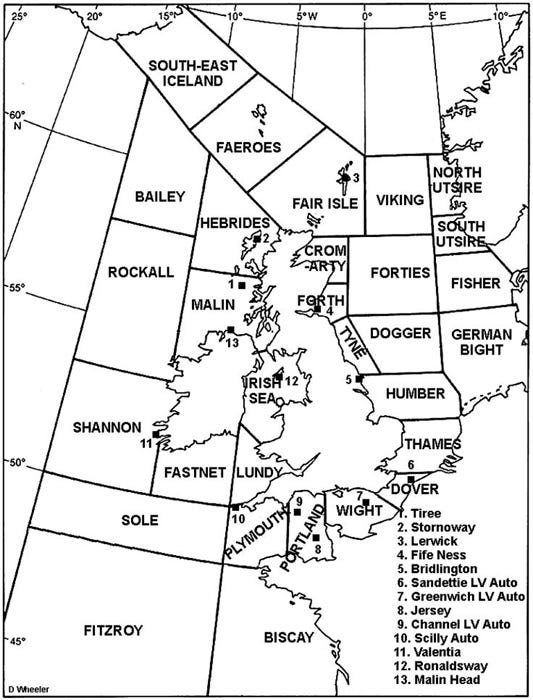

above: shipping areas for the Shipping Forecast. Well worth a listen on Radio 4.

These hurricane force storms had begun along the channel and gradually hit almost every area, except the Irish Sea. The storms tracking in largely from westerly or south westerly directions, Ireland provides a bit of an obstacle from the perspective of Cymru, taking the top end off the wind.

Then, the last storm of the season, in late February, with the wind coming in from south of south west, enough of a deviation to clear Ireland and howl almost directly up the Irish Sea, giving us what, as far as I know, was the first Irish Sea Hurricane Force 12 storm. If I remember rightly, it was on that forecast that the announcer gave out five Hurricane Force 12 warnings and remarked, in a very subdued voice, that he had never given so many before in a single forecast.

Coming as it did, after half the annual rainfall had fallen in under three months, the result was pretty devastating locally, with probably thousands of trees down in Coed Y Brenin, including hundreds of excellent, mature pines further up our road and similar numbers on Allt Ffridd Goch, the steep eastern valley side of the Afon Wen. This also caused a major landslip here that blocked the single track road below and required the clear-felling of the whole hillside, closing the road for two years. The highest wind speeds of over 100mph were recorded on Pen Llŷn3, the Lleyn Peninsula, forming the northern boundary of Cardigan Bay and hence directly in the path of the hurricane.

The idea that Storm Eowyn was a "Once in a generation event" was further contradicted on the same radio channel by another BBC expert. This was in relation to Ireland having been issued with its first Red Weather Warning. She described how global warming was pushing up the speed of the jet stream which in turn was influencing wind speeds at lower altitudes, hence these type of storms would become more likely. Perhaps the generations are getting shorter...Whatever, to speak in terms of "once in a lifetime" storms or "100 year" flooding events now seems disingenuous.

In regard to the question "are storms getting worse?" I found LynnCady's piece asking if hurricanes in the US are getting worse very helpful here. I think the approach she uses has a general relevance to extreme weather events of different type. Basically she asks three questions, the answers to which are "No, Yes and Maybe"; Lynn Cady goes on to explain that the answers depends upon what and how you measure.

To put it simply here, the first question she asks is has the event caused more loss of life than in the past and the answer is generally "no" because our warning systems are much more effective. However, a recent exception to this was the terrible flooding in Valencia which resulted in a lot of deaths because warnings were too late or inadequate and the downpour so intense (upwards of 400mm in 24 hours) that waters rose with terrifying speed. Its worth pointing out that with that much rain falling so rapidly, anywhere can be flooded. One of the things that the Radio 4 expert pointed out was that given global warming, higher air temperatures can hold more moisture and when the air cools, the resulting rainfall comes at much higher rates than in the past.

Back to the LynnCady method, If we next ask how much damage the event caused, measured in terms of damage to infrastructure and property, then generally the answer to is it getting worse is "yes|", mainly because there is now a lot more infrastructure to trash and it is much more expensive to fix.

Finally, if we then ask whether the event was worse in terms of measurable variables, such as wind speed, rainfall and the like, then the answer is "maybe". So for example, although Ireland registered their highest wind-speed ever (as in, since records began), in Scotland Storm Eowyn was considered to be the worst storm for at least ten years and here in South Gwynedd Eowyn was nowhere near the wind-speeds of our hurricane of 2014.

above: Natural Resources Wales busy clear-felling more larch on Mynydd Penrhos in advance of the tree disease phytophthora ramorum which really likes larch. This means non-larch species aren’t felled, like the clump left here. Note the deep ruts made by the forwarder making repeated journeys to collect logs cut by the harvester.

One major consequence of the damage to infrastructure of Storm Eowyn was the loss of power (electricity) initially to over a million properties and even now, over a week after the storm, over a hundred thousand homes are still without power. As I've mentioned before here on Substack, increasing reliance on electricity in the UK for primary heating, such as Air Source Heat Pumps is dodgy due to the often aged and fragile distribution network and storms like Eowyn are a regular reminder of that.

above: same clump after Storm Eowyn…duh! Close planted at two metre spacings, further in-filled by self seeding western Hemlock, these trees have never seen any management meaning they are ridiculously thin for their height and have very restrictive roots systems and when left exposed by neighbouring clear felling, tend to fall over or snap. What a surprise! Not….Note the forwarder parked up on the right.

Given that rather than annual green house gas emissions gradually reducing each year, 2024 emissions actually went up and also broke the record for the hottest year so far; further, given that the US's new president looks unlikely to do anything about it and is introducing policies that will increase emissions even further, we have to face the facts that storms like Eowyn will likely become more common and yet more violent. So be prepared to batten down those hatches folks, we're in for a bumpy ride.

Thanks for reading.

One of the reasons for the delay in this piece, apart from the usual one of low power, was my memory. I had thought that "our" hurricane occurred about six years ago (indeed, I think I've said as much in the past, here on Substack- oops, sorry), but when trawling though my diaries for details of this event I couldn't find it and searches on-line came up with nothing. Then I remembered that one of the consequences of getting old, apparently, is that we tend to telescope our memories, thinking things happened much more recently than they actually had.

So it was only when searching more widely on line that I tracked down that fateful winter to 2013-2014 when the UK was hit by storm after storm of genuinely scary power, delivering vast amounts of water and very high winds. Some details of this remarkable sequence of storms can be found here

OK, that's it. Konsk next. Till then, please feel free to comment and take care, it can be windy out there. Hwyl! Chris.

October 2023 to March 2024 was the second wettest such period since records began and February was the warmest February on record here in Cymru.

The Shipping Forecast, as the name implies, is primarily intended for folk at sea and gives out forecasts for named shipping areas that make up UK coastal waters. However, once you are familiar with the descriptions, it becomes a very useful way of building up a more complete picture of the current and expected weather around the UK.

The forecast begins by listing the areas with gale warnings then describes briefly where major weather systems currently are before giving the forecast for each individual area using the same pattern of wind speed (using the Beaufort scale), wind direction, rainfall, and visibility. The forecast begins with the areas to the north and moves around the coast in a clockwise direction. You can find more details on Wikipedia.

The accent over the ŷ indicates a lengthened vowel, something like ee. It’s spelled Lleyn in English, as in The Lleyn Peninsula which sticks out about thirty miles into the Irish Sea. In Cymraeg, the accent is called a To Bach, in English, Little Roof. Nice- I love Cymraeg!

My apologies. I have incorrectly described the chart showing 2024 rainfall, temperature and humidity. It actually shows daily minimum humidity and daily maximum temperature (not minimum). Sorry about that. Chris.