The Real Coed Y Brenin

The Early Forestry Commission and the Erasure of Social History. Part two

In my previous piece on The Real Coed Y Brenin, I covered the early history of Mynydd Penrhos and how it was chosen as the site of one of the Forestry Commission's first plantations which became Coed Y Brenin, or The King's Trees. I described the tyddynwyr, the smallholders who were there first and had gradually created their few acres of fields from the rough terrain.

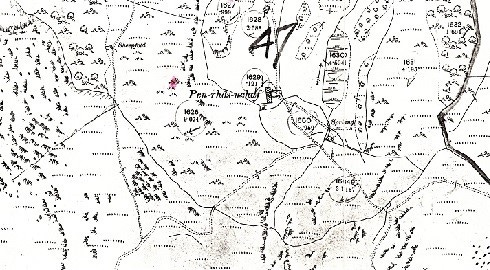

above: Mynydd Penrhos before the plantation

For them to eke out their subsistence livings, they took advantage of other land types around them, evolving patterns of usage that became traditional rights, often reflected by name. I'll describe some of these land types here as they contain clues or hints for future design. (I've also given some indication of pronunciation, as footnotes, for those of you who may be interested).

Mynydd1 or mountain provided grazing during the summer months and allowed sheep and cattle to escape the flies. Mynydd Penrhos is only a very small mountain at 764 feet, to most people only a mountain in name but it contains and is bordered by distinctive, steep-sided hills which reflect the complex, fractured geology beneath. In Welsh, although many hills are named “bryn”, meaning “hill”, (as in Bryn Coch or Red Hill, for example), there are also what we would think of as a hills that are called moel2 (plural moelydd) meaning bald and it is interesting to consider how that name might have arisen.

above: Moel Friog, once “bald” before the plantation and soon to be bald again…

We can imagine a time before extensive grazing, when most hills would be covered with vegetation, probably a mix of what we would call scrub and trees, giving them a shaggy appearance. Once a hill was denuded by a combination of felling for material followed by grazing, particularly with sheep, it would take on a relatively smooth appearance compared to other hills and stand out, hence meriting a term like “bald”. So on Mynydd Penrhos both Bryn and Moel appear in names. Each Moel was named according to the farm that held rights over it, hence Moel Friog, Moel Dolfrwynog and so on. Of course, as the process of deforestation continued, as all hills became “bald”, the term would largely lose its meaning, even more so now that the trees of Coed Y Brenin have once more given them a shaggy appearance.

A similar naming process is found with another land type, namely “allt”3 (plural elltydd). In Vera's “Grazing Ecology and Forest History”, which I have mentioned before, he suggests that steep hillsides were difficult terrain for large herbivores and hence would tend towards trees and we can see an indication of this in the original meaning of “allt”, as a steep, wooded hillside, often descending from a moel. When I first arrived in the Dolgellau area and began exploring the tributaries of the Mawddach estuary, many of these steep sided valleys supported formerly coppiced oak or hazel, so an allt would have provided a tyddynwr with a useful source of brushwood for their fire or material for hurdles and the like.

above: footpath traversing the scarily steep slope of Allt Fridd Goch, looking across at Allt Moel Dolfrwynog on the Afon Wen fault.

It is worth pointing out that until the time of cheap, rolled steel and machine production techniques, a saw was a time consuming and hence an expensive item to make, beyond the reach of most tyddynwyr. An axe on the other hand was more easily made by a local blacksmith, meaning that brushwood or underwood, that is, small diameter, coppice wood, was available to the tyddynwyr. The idea of sawn logs for a fire was a rich man's game. The elltyd were similarly named for the farms who held rights over them and often include the moel they descend from, such as Allt Moel Dolfrwynog.

Cors (plural corsydd) or bog was favoured especially for cattle, the water meaning that the temperature stayed slightly higher than that of the surrounding land. This meant an early green bite in spring and a slightly longer growing season in the autumn and it is interesting to see today the return of cattle to the uplands, after many years absence and to find them knee deep in bogs, happily munching. Its worth pointing out that the presence of cattle in the uplands, greatly restricted the growth of bracken, which cannot stand trampling and compression. Several of the older folk confirmed that when the working horses and cattle grazed extensively, there was far less bracken.

above: cors or bog on Mynydd Penrhos, challenged by encroaching birch and willow. This bog was revitalised in the mid 1990s by local ecologist and, at the time, Forestry Commission Conservation Ranger, Dr. Martin Garnett (the first in Britain and probably the most over-qualfied ever!) who arranged for blocking of drainage and raising the water table.

Bogs were also vital for the tyddynwyr as a source of fuel, peat, for their fires and there are several turbaries, or peat cuttings areas, with their associated drying mounds, on Mynydd Penrhos. Early accounts describe the farmers' peat fires as a “mynydd o fawn”, a “mountain of peat”. These fires burned for most of the year, the continuous warmth creating enough of a temperature gradient to drive out the worst of the damp. An outer layer of dry peat restricted the oxygen supply, keeping the inner core smouldering and this outer layer could be opened skilfully to produce and control flames for cooking in pots hung on chains.

Finally, ffridd4, perhaps the most interesting and certainly the most diverse and species rich land type. I have treated fridd in some detail in another piece which can be found on my web site, here. For now, following on the work of F W M Vera, we can think of ffridd as the remnant of something like the original vegetation of much of Britain, a complex mix of species rich grazing, herbs, shrubs and trees that was grazed at specific times by a variety of livestock. By thoughtful management of the grazing (the times, types of animals and numbers) the tyddynwr could maintain a complex system, balanced dynamically between forest and pasture.

above: ffridd remnant near Cross Foxes. Very little fridd now survives in anything like its previous, managed state. The picture does give a good indication of the diversity of species, topography and habitat which mde ffridd so special. It also gives us a clue as to what large parts of Britain might have looked like before farming took hold and hints at future landscapes.

I have described ffridd as a traditional agro-forestry and it provided the tyddynwyr with multiple opportunities for harvest, from small timber to larger beams (when a mature tree might be felled), from berries to herbs, as well as grazing for livestock. As a land-type that also provided shelter, it was often used if an animal was sick, allowing for self-selection of plants with appropriate medical properties. An extension of this was the ysbyty, or hospital field, usually small and surrounded by hedges. This well sheltered pasture provided good opportunities for a sickly animal to self medicate, through selecting appropriate plants from the species rich pasture and hedgerows.

above: 1901 map, pre Coed Y Brenin, showing one of the Mynydd Penrhos farms, Penrhos Uchaf.

I was fortunate enough to meet folk who had rented these farms and talk with them about their experiences. The most common response was that the work was hard but the community was amazing. Much of the work was drudgery, the annual repetitive tasks of, for example, cutting peat, clearing stones or making rush lights. Yet these tasks were lightened because they were not carried out alone but by groups, whether or men or women or children or mixed and the talk, stories, songs, joking and such that accompanied these tasks, were as important as the task themselves, for this is the glue that creates and binds a community together, providing a sense of identity and connection with people and place.

above: the ruins of Penrhos Uchaf.

Mrs. Jones, in her nineties when I spoke with her, had rented one of the farms on Mynydd Penrhos for ten years, beginning in 1930, when the plantation had been started but had not then engulfed all the land. She listed for me the livestock they kept; it was most definitely a mixed smallholding and I was surprised by the number of cattle, at fifteen, two of which were milked. Milk and oats in various forms was the staple diet of the rural poor in Britain, known by various names such as flummery, chowder, crowdy or just a mess of oats, depending upon where you lived. Cream went for butter with the whey to feed weaner pigs.

They had only about thirty sheep, for wool and meat plus the usual variety of fowl- chickens, ducks and a few geese, providing eggs and meat. This is more or less the same as the stock on my maternal grandparents farm in Cumbria and no doubt most of the rest of rural Britain at one time.

above: another ruin of a farm house.

The tyddyn was not large enough to support breeding pigs and certainly too small for a horse though they did borrow a pony and sled at times to haul peat. They also carried vegetables down the steep slope to the weekly market in Ganllwyd which was where they raised the small amounts of hard cash they needed.

She described how after ten years there, they left carrying with them on their backs the same possessions that they had carried there on their arrival, nothing more, nothing less. This, in a nutshell, is subsistence farming- you grew enough to feed and cloth your family with enough to sell to pay your rent and that was all. These then were the tyddynwyr.

In the next part of The Real Coed Y Brenin, The Coming of the Trees, I'll tell of how the Forestry Commission erased the entire community of Mynydd Penrhos and beyond, such that even farm names have disappeared from the Ordnance Survey maps, along with the memory of the families who lived there.

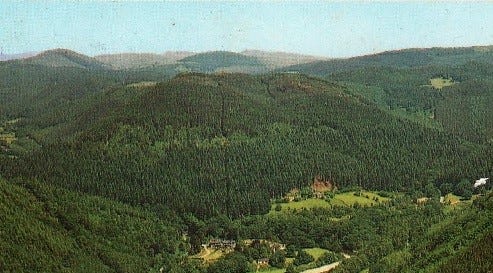

above: Mynydd Penrhos and Coed Y Brenin rolling out beyond, a roughly 19,000 acre plantation of exotic species.

Thanks for reading. Please feel free to leave comments- I appreciate all of them. I intend to do one more piece on The Real Coed Y Brenin, then leave it for a bit but please, let me know what you think! Many thanks. Blwyddyn Newydd Dda i chi gyd!

Mynydd

when two y's appear in a word, they usually follow this pattern, munidd; the u as in but, the i as in big. The same pattern is found in tyddyn.

The dd in Cymraeg represents the same sound we find in the th of English the and then.

Moel, the oel as in oil.

Allt. Here’s what Nesta, my excellent Welsh teacher told us. Make a hissing sound and notice how your tongue closes off the sides of your mouth, allowing the hiss to escape from the front. Now do the opposite, the tongue closing off the front of the mouth and the hiss escaping through the sides. With the ll in the middle of a word, as with allt, that’s pretty much all you have to do. At the start of a word, like llan, you do the side of the mouth hiss and pronounce an l.

Ffridd. Ff in Cymraeg denotes the single f sound of English (a single f in Cymraeg is equivalent to the English v). The i in Ffridd is a long vowel, so its more like freeth, with the th as the th in the

fascinating, again!