Odd thing with writing on Substack, I usually have at least two or three pieces lined up and waiting to be finished, yet often as not some other piece will intrude itself upon my consciousness and I'll be forced to turn my attention to it. Such is the way with this, on the Tao and Taoism.

I'll say immediately that I do not consider myself to be a Taoist or an expert on Taoism, just that Taoism is probably the closest I'll get to any sort of formalised spiritual practice. In a similar way, although I was greatly honoured and pleased to be awarded a permaculture diploma, way back in 1994 alongside the late, great Phil Corbett and the equally great but not late Misrule, I don't really consider myself to be a permaculture designer, as such, its just that permaculture design is probably the closest I'll get to any sort of formalised foundation for action in this world. So with that in mind, here's my personal take on Tao and Taoism.

To begin, the first rule of Tao is that you do not talk about Tao...

...sorry, couldn’t resist. More accurately, it is said that the Tao that is spoken of in words is not the true Tao. So I have set myself a bit of a challenge to write, in words, at some length about the Tao…

That statement reminds me of one we use in permaculture design, that the map is not the territory. The map is an abstraction which looks at the territory from a very particular perspective. We can look at the territory from many different perspectives, such as geology, topography, soil types, species distribution, climate, rainfall, occupants and so on and so on but really the territory can only be experienced. So too with the Tao.

Tao or Dao means a way, originally a watercourse way which suggests a flow and concepts such as going with the flow. It crops up in various names, such as Judo, (the do is dao or tao), “the gentle way”, or aikido, meaning something like “the way of harmonious spirit”.

Its easier to talk about Taoism first and circle around The Tao, as though it were a strange attractor, guiding us without us ever quite touching upon it.

So Taoism is probably the least popular of all the spiritual traditions. Why? Because it makes absolutely no promises- no forgiveness of sins, no resurrection, no afterlife, no glamour, no congregation, no ranking, no karma, no reincarnation, no deities or demons other than those in our own heads. All it offers is a set of practical exercises, some sound dietary advice and a few texts containing stories and aphorisms that suggest ways of dealing with the travails of ordinary life. Without actually promising it, by following those three things, you may live a long life, or not.

The practical exercises are some of the oldest recorded in history, going back at least 3,000 years. There are three main physical traditions, namely Tai Chi Chuan, Chi Kung and Da Chen Quan (there are many different ways of spelling these practices in English!). They are often described as the origin and foundation of all the martial arts and Da Chen Quan is described as the most powerful of all martial arts. Interestingly, in the same way that the principles employed by permaculture designers were abstracted from close observation of natural systems, many of the exercises and the postures found in Tai Chi are taken from observation of animals and birds, especially the long lived ones.

The diet is similarly ancient and basically encourages frugality, a non-reliance on grains as a staple and the avoidance of overly rich, processed or highly spiced items. It emphasises the eating of simple, nutritious foods such as leafy plants, fruit, nuts and is largely vegetarian and in some schools, vegan.

So how did I get started on this course, or rather, this way?

I had an atheist upbringing and by the age of ten knew more about Greek and Roman gods and goddesses (from my mother) and Beowulf and the Icelandic sagas (from my father) than about Christianity and the trinity. I knew J G Frazer's The Golden Bough better than the Bible and was interested in magic and religion as psychological phenomena rather than an actuality or something to follow.

Back in the 1970’s, when I was at college in Aberystwyth, I would spend time in a very good second hand bookshop towards the top end of town. I was mainly looking for second hand versions of the set texts for drama and classical studies but I tended to read around the subjects, sometimes straying quite widely.

One afternoon I picked a large format paperback off the shelves and skipped through, looking at the nice black and white photographs, Chinese characters and reading bits of the text which struck me as...odd but interesting, somehow captivating. The book was the so-called Inner Chapters by someone called Chuang Tzu, a text that I learned much later is considered to be one of the fundamental Taoist texts. Anyway, without really knowing why, I bought it, took it home and spent a year or so both reading it repeatedly and also just dipping in to it now and then. I began to see some sense to it and things I could use.

From Chuang Tzu I got ideas such as “going with the flow” or “bending with the wind”, the idea of never presenting a hard front or challenging obstacles head on. I liked his description of the butcher who only needed to sharpen his knives once a year because he never cut anything, just passed the blade between sinews and joints. Or the tree that survived because the trunk was too twisted to cut for boards, the branches too bent to be used for joists. In other words, it appeared useless and so was left when all the others were felled.

Some years later, when Lyn and I had found our place, in a stand of Corsican pine just across the road from us, I noticed a tree that had grown two leaders, probably several decades before, both of which had turned slightly inwards, like a giant tuning fork or a very big but narrow wishbone. It was a beautiful shape and I was very tempted to cut it down and steal it, but I didn’t.

Some time later the Forestry Commission Cymru felled the whole stand and hauled them off for stakes and sawbars and I wished I had stolen the twin leader but then, walking through the wreckage left behind and lo, there it was! It had been left because it wasn't a straight trunk, it was useless to them! Delighted, I hauled it home1 and it lay against a wall for some time before I realised I could turn it upside down and use it as the gateway to our first garden.

above: the “useless” twin leader, left behind after clear felling.

Moving forward to the 1980’s and Dolgellau, among a whole group of new friends I met Sion Devy, who helped inspire us to form a local group and set up a wholefood coop. He also ran a very simple introduction to Tai Chi one afternoon in the Neuadd Idris in Dolgellau, during which he taught us some exercises and a little pattern of movements, a simple form, to take away with us and practice. It was during this session that I learned that Tai Chi was something to do with Taoism and that Taoism was also known as “The Way of Nature”.

Now I was really intrigued. Lyn had opened my eyes to the close observation of nature in the 1970's and I had begun the natural re-vegetation project I was calling Argel, sanctuary. For six years I walked around this small site almost every day, noting the appearance of individual trees and their various fates- eaten or browsed by fallow deer, sheltered by gorse, growing to overshadow the gorse and each other. Noting also how I had interacted with and steered the re-vegetation, inadvertently at first, by my walks, creating paths that the deer followed, by moving bramble runners to one side, having a pee and so introducing hits of nitrogen and so on.

Sometime in the mid 1980’s I heard of a Tai Chi class starting up in Machynlleth, some twenty miles from us, run by a woman called Mair Tudor Lewis and I signed up. It took two years for her to teach us her form and although I had to travel furthest of all the group in my trusty Reliant Robin Supervan III, I never missed a session; I was well hooked. Mair was a perfect teacher for me and I practised the form at least once a day for the next two years.

above: view from the gate in 1986. Sharp eyes will find me practicing Tai Chi, just to the right of centre.

Since then I've had several different teachers and learnt or re-learnt various forms. A form is a series of postures or stances and the movements that connect them together. You learn a form by adopting each stance with your teacher getting you to put your hands and feet in particular positions and then moving from one posture or stance to the next one. So to begin with, your attention is fixed on what your hands and feet are supposed to be doing but as you practice, you gradually withdraw your attention from your extremities back into your body and ultimately into your core, your physical centre, known as the Tan Tien, a couple of inches below your naval.

I began to realise that this centre is where all movement begins, that moving the centre is what then moves the arms and legs. That and breathing; breathing in naturally draws the limbs inward, breathing out moves them out. What I really liked about learning Tai Chi was that I could use it in real, practical situations. So raking, digging, sawing wood, washing up, all can be used as exercises based around the movements of Tai Chi- if you've seen the film The Karate Kid, you'll know what I mean; think wax on, wax off, brush up, brush down.

In the late 1980’s I attended my first permaculture design course and found that the foundation or roots to the whole system are observation of nature and natural systems and working with nature not against it. This struck me as being very Taoist, the way of nature. Add in the permaculture design aphorism of allowing systems to demonstrate their own evolutions and we are at the heart of the Taoist practice of non-interference. So even if our designs seem to go off track, we let them run as they choose, for they might lead to even better systems than we had originally envisioned.

This had been my instinctive approach with Argel, where I had at times been so tempted to interfere, but didn’t. For example, I had concerns at one point that in some places bracken might become dominant and itched to step in and cut it, but didn’t. And there was no need, for trees grew to shade it out. Or that the masses of gorse that appeared would persist but they didn’t, as trees grew up through the plants, opened out their boughs above, shaded it out and it collapsed to next to nothing, to fertiliser and mulch, in just a matter of a few seasons. So I could have committed myself to endless, pointless effort, trying to achieve something that nature would do anyway and far better than me.

above: view from the gate 2007, just over twenty years on. The foreground is a result of non-interference, allowing systems to demonstrate their own evolutions, otherwise known as The Way of Nature.

There are many schools of Taoism and I have as yet no desire to study any of them in any great detail. Knowing what I have learned so far seems sufficient to reinforce my practice of permaculture design but it is interesting to look at and think on some of the practices and how they can be applied to permaculture design. I have listed nine of them here.

Nonaction

Softness and weakness

Guarding the feminine

Being nameless

Clairty and stillness

Being adept

Being desireless

Knowing how to stop and be content

Yielding and withdrawing

Finally, to close this piece, these are the main books relating to Taoism that I have enjoyed and found useful, in the order, roughly, that I discovered them.

Chuang Tsu, Inner Chapters. Gia Fu Feng and Jane English. Knopf/Vintage 1974

This is book that grabbed my attention. I still find it both insightful and odd, parts of it remaining mysterious, even after half a century...bit like life really.

Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching. Gia Fu Feng and Jane English. Wildwood House Ltd 1976

The other, early Taoist text and the better known, along with Confucius. Not as mysterious or odd as Chuang.

Alan Watts, Tao, The Watercourse Way. Pelican Books 1979

A good, accessible introduction to Tao. Alan also writes in a similar accessible style about Zen. The Zen Buddhists liked the practice of Zhan Zhuang (described below) as it was similar to ZaZen, a sitting meditation where you simply focus on your breathing.

Deng Ming Dao, 365 Tao Daily Meditations. Harper Collins 1992

I stumbled on a copy in the Dolgellau Red Cross. It offers a daily word, Chinese character, a short verse and a paragraph or so of text explaining the word in more detail. I like the daily ritual and at the end of the year, just start again. I underline the bits that jump out at me.

Lam Kam Chen, Stand Still - Be Fit, the ancient art of internal energy. Chanel Four Television 1995

I found this amongst my late father-in-laws books. It's a pamphlet published by Broadcasting Support Services to accompany the Chrysalis production for Channel Four of the same name, first broadcast in January 1995. It provides a good introduction to the Chi Gong exercises known as Zhan Zhuang (pronounced Jam Jong), "standing like a stake" or a post or a tree, depending upon who translates it. You can find a series of short videos of Lam Kam demonstrating and explaining the stances on You Tube. Lam Kam is the current grandmaster of Zhan Zhuang and appears to be a lovely man.

above: a young Lam Kam Chen demonstrates one of the stances of Zhan Zhuang.

I used this pamphlet to begin a daily practice of Zhan Zhuang which I have been following for just over five years now. I continue to practice because it works for me - my stamina improved dramatically, as did my posture and my breathing has deepened considerably and is much freer and easier.

In Chinese, there are five elements, the same four elements of Earth, Water, Air and Fire as in the European tradition but with the addition of wood. To the Chinese, wood represents the life force, whether the wood is in the form of a living tree or a stake or post. I think Lam Cam has used a tree, rather than a post, in his work as we would tend to see the post as dead. Interesting that the life force is missing in the European tradition. Bill Mollison pointed out this omission to us on his advance design course at Ragman's Lane Farm in 1991.

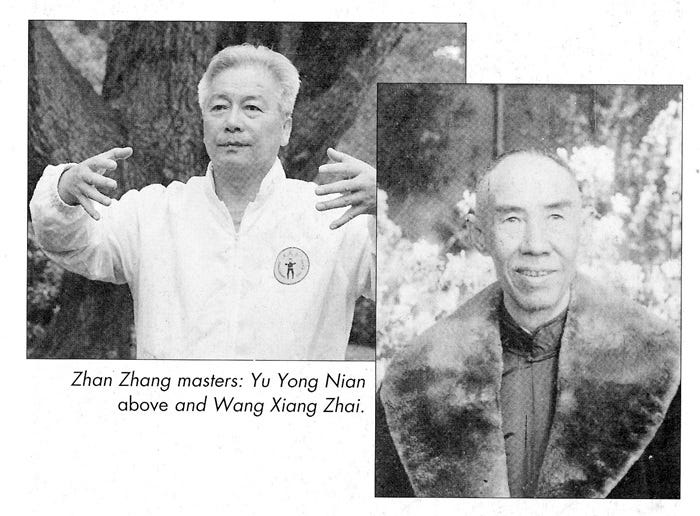

Yu Yong Nian, Zhan Zhuang. China Martial Arts Ltd 2006

The late grand master of Zhan Zhuang who appears in Lam Kam's videos and is another lovely man. Trained as a doctor, the professor provides clinical evidence for the benefits of Zhan Zhuang as well as greater detail on the exercises. Very useful if you wish to really get into the technique.

He also describes stances for people who are confined to bed or a chair and emphasises that Zhan Zhuang is both a preventative and a curative exercise. Also, that it is one of the very few physical exercises that requires no interference from the mind. One good clue he provides is to simply count your breaths as you stand in each stance and don’t force the breathing- it will improve quite naturally. That's it. Simple. The practice is also used as a foundation for the martial art Da Chen Quan.

Deng Ming Dao, The Wandering Taoist. Harper & Row 1983

A remarkable story or a remarkable man and his equally remarkable training in the martial arts, living in the late 1800's through the turn of the century. As an example, when he and his fellow students were in their very early teens, their sensei (teacher) began teaching them how to fall by standing them in a line with their backs to a ten foot (3 metre) drop, then he walked along the line, pushing them off one by one. The sensei offered no advice or guidance but continued until he was satisfied with their progress then repeated the whole thing from a higher drop; and so on...If you've seen the film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and thought the fights in the tree tops were ridiculous, think again...

There are plenty of illustrated books on various Tai Chi forms but I think one needs a teacher and a group to really get to grips with and learn a form. Working with a learning group gives an added incentive to practice and working with a teacher means you get immediate feedback on your performance. On the other hand, I have found that it is more possible to learn Chi Gung exercises from a book, especially when combined with videos by acknowledged masters.

That's it. Turned out a bit longer than I expected but such is the way! Many thanks for reading. Next time, finally, the last episode in the Great Takeover of the Place, a thread in that meta-pata-fiction taken from the Konsk Kosmology. Till then, take care all. Hwyl! Chris.

Back in the day it was possible to go into the Forestry Commission's District Office in Dolgellau and pay £10 for a “ticket” which allowed you to scavenge timber left on a clear felled site. This was a very good practice, reducing the fuel burden in the plantation and allowing locals to get some benefit from it. I fed our fire for many years from such scavenged fuel. As hardwoods were of no interest to commercial foresters, these would often be felled along with all the softwoods and then left. Of course, to me, such wood was like treasure!

I found this piece really interesting Chris. On a visit to china many years ago I watched locals practicing Tai Chi in the park near my hotel - I could see them from the windows or walk over for a closer look - and was fascinated. I am particularly taken by your linking it to Permaculture which I use a lot in all aspects of my life. You have inspired me to look into it all more deeply so thank you for the book suggestions.

Hi Chris, nice read, hopefully you will recall that i have commented before regard 'TCMA' (traditional chinese martial arts) that covers all of the 'internal' arts including tai chi chuan (great ultimate fist). I'm still practicing with Wutan and as well as 5 different tai chi forms (schools) we also practice Bagua, Hsing-i and Baji - Bagua is based on the 'i-ching' trigrams (the trigrams are also used to explain the position of effort, for want of a better description for the eight gates of power in tai chi practice with the broken and unbroken lines representing yin/yang) - i picked upon your mention of the 5 elements and animals to talk about Hsing-i chuan(mind intention fist) and its practical applications - in 5 elements Hsing-i the 5 elements are each represented by a 'fist' or posture/application that both defends and attacks simultaneously - each element gives 'birth to the next' but then there is also a 'destructive' cycle that can be applied. Metal gives rise to water (condensation) that gives birth to wood. Wood leads to fire that becomes earth (ash). Once the 5 element fists are understood there are then various 'animal' forms based upon 12 animals and their practice does indeed mimic both movement and characteristics (after all who has observed a dragon?) and each is quite strenuous to perform physically - you get very strong legs very quickly, especially 'dragon' which involves leaping directly upwards from a very low posture, swapping leg positions and landing into a very low posture. Relating some of this to permaculture practice i'm minded of the 5 directions in tai chi practice - advance, retreat, look left, gaze to the right and the constant 'central equilibrium' around which everything else moves but with stable dynamism - maybe what Holmgren was thinking with 'observe and interact'? As a footnote the chi kung exercise you refer to is an excellent example of applied central equilibrium - it's included in all of our classes preliminary warm up exercises.