Consciousness is a subject that I have thought and written about many times over the last half century or so and what follows is a subset of that, following an experience of my son, which I relate below. I shared this thinking with my father and we would regularly return to it in our conversations; his contributions are embedded in what follows. I throw it out here as work in progress and welcome your thoughts and comments.

Internalising the speaking voice for the first time

Once I was bagging goods in a wholefood co-op in Dolgellau, with my then young son, Sam, aged about three and a half. I noticed he'd gone quiet which can be a bad sign- what trouble has he got into now? Then he came over with a look of barely suppressed excitement and told me, very proudly, that without saying anything out loud, he had managed to say a word in his head (the number "four", I think). He went on to explain that he had to move his lips but he didn't make any sound.

From here he quickly went from reading out loud (to me and others), to reading in his head but still moving his lips, to then fully internalising his reading without needing the physical support of tongue or lips.

Vygotsky’s experiments with children internalising speech

When I told my Father about this first internalised word, he in turn told me about the Soviet psychologist, Vygotsky and his experiments with children. Vygotsky and his collaborators had got children of various ages to carry out tasks like "get the tiger into his cage"1.

This required controlling the tiger's movements on a screen by turning two dials, one for up and down, one for left and right, in order to manoeuvre the animal into its cage. Vygotsky found that, from age of about three or so upwards, children accomplished this task with little difficulty but younger ones usually struggled and failed.

However, if these youngsters were accompanied by an elder sibling who remained silent and offered no help, they could manage the task. What was happening here? It was because when accompanied by a familiar other, the youngsters would then talk aloud about what they were doing to their sibling, describing the movements of the tiger in what we as adults may think of as the childish babble that accompanies play.

Along the lines of, "oh the tiger's gone to far. come back, come back, here she is, coming back, now up, up , no she's gone to high, come down tiger! etc. etc. until they accomplished the task.

Thinking out loud

They are actually thinking out loud, organising the necessary sequence of actions required to get the tiger into the cage. By the age of about four, most children have learned, like Sam did, to internalise the spoken word: they could carry out the task silently, or perhaps mouthing just one or two words.

Thus we first learn to think in words by speaking out loud and our early experiences of learning to speak out loud are co-operative, as in a conversation; it requires at the least one listening other.

Thinking out loud in earlier cultures and societies

If we consider this alongside the simple notion that our individual development mirrors in some way our social and cultural development as evolving humans, we might speculate that in an earlier phase of our cultural and sociological development, all our early thinking would be verbal, in the presence of another or others; that is to say that a listener was required for an individual to be able to think, out loud.

This may be necessary, for example, if we are attempting to learn or communicate the sequence of events or actions required in order to achieve a certain goal, (such as the making of a flint axe) or (maybe, if the method is similar) to report a particular experience as a narrative. These sequences of words and presumably accompanying gestures, could be recorded in song, reinforced with dance, body decoration and all the techniques and strategies of ritual and thus become more easily transmissible.

This last point is significant, because one of Vygotsky's successors, Piaget relates two stages in our ability to organise our activities.

The earliest, in infancy, he called sensori-motor, because the infants were, for example, reaching out to grab something (a biscuit, a toy) and convey it to their mouths. As this became a familiar trick, he suggested they had developed ‘sensori-motor schemata’ which coordinated the muscular movements, the eye control, the sequence of events. This stage of coordination did not rely on words; their use as a more refined control came later.

Neuroscientists and others suggest that language in words reinforced the already existing method of sensori-motor control, at least at first. If so, taken together, these two processes gave access to the information (for example, a food preparation process, a sequence of actions required to make something, or identification of correspondences between social and environmental events) and could be transmitted and recalled orally, for example by singing the song, probably with accompanying gestures.

Thinking out loud as a collaborative experience

Further, in tribal cultures, everything is talked about and happenings relevant to the whole community are discussed by the whole community in all its various groups (young girls group, young boys group, elder boys, elder girls, men, women, elders etc.) as well as the whole tribe. Thus the thinking out loud is a collaborative enterprise precisely managed by custom and ritual, from which the one voice of the tribe may be discerned and a decision made, or often not.

Interestingly, tribal peoples seem to be happy not to come to a decision if it is difficult but are prepared to defer it for future discussion. This process was reflected more recently at the Teepee Valley Community in Cymru, several times, regarding whether or not to allow dogs on the site; the decision was regularly deferred as no final agreement could be reached.

In contrast, the current culture is very insistent on the individual and the individualising of any contribution but seems that in societies that emphasise collective efforts, the pool is more focal than the individual contribution. If so, talking and thinking are perceived as an amalgam of voices, a summation of a collaborative process.

(I will mention here Misrule's recent post regarding Polis software as an aid to consensus decision making.)

Interpreting the internalised voice

From the individual perspective, at a phase of development where language has developed but is purely external (vocal), at some point an individual would learn to hear a voice in their head (internalised), as Sam did. How this voice was interpreted would depend upon the culture and society in which they were embedded. The internalised word might arise as a result of a conscious attempt to do it, as with Sam, or as a spontaneous occurrence at some point in our evolution. There may also appear to be several voices.

Very early in their games children learn to role play in the voices of the participants – parents, teachers, and so on. They are enacting a persona – imagining becoming another person. To some degree, that person and their voice has become internalised in its turn. In hunter-gatherer societies (so-called), a person as a hunter may speak in the voice of the animal they have killed, or as a gatherer in the voice of the tree whose fruit they wish to pick, thus establishing a relationship between them. And in the early cities we know that there were rituals where participants enacted the roles of the gods, the priests, the multitude (the chorus in Greek drama).

Succession in interpretations

If the first occurrence of this internalised voice arises unbidden, the individual might ask to whom does the voice or voices belong? The interpretation will be steered by the culture and society in which the individual is embedded.

So the voice or voices may be interpreted as emanating from the small spirits of the place (as in the pool, bend in the river, tree on the bank, a rock, that jackdaw etc.), or the spirits of the ancestors (also of heroes, malevolent demons, guardian angels, totem animals and the like), or functional deities (gods and goddesses of thunder, farming, hunting etc.), or monads (God, the Goddess, IHVH, etc.), or be labelled as (only) our own internalised voice.

Its important not to presuppose that accepting that the voice was our own is the only correct interpretation; it is rather just a different way of perceiving the voice and no more correct than any of the others, given each ones different supportive context

Under special conditions, which the prophet or oracle, say, might seek out – like a dark secluded cave, suited to a meditative trance, perhaps with vaporous fumes or the addition of drugs, she or he becomes a medium for the voice of the Other, which possesses her.

These ideas raise many questions

When did it become commonly accepted that the internal voice was "just" a personal voice, an internalisation of an individual’s vocalised thought processes rather than external entity or entities?

Are there examples from earlier times of individuals developing an internal voice ahead of others (early adopters) and what difference would this make within a community? Would it give them an advantage in some way?

What differences were created between communities for those which were further ahead in internalising their voice(s) than others?

Correspondences

On a seminal Advance Permaculture Design Course back in 1991 or 92, Bill Mollison described to us how tribal people showed great concern for individuals who hung back from the group and thought for themselves, rather than joining in with group thinking. Efforts would be made to draw the individual back into the group. They perceived this "thinking by one's self" as potentially dangerous. We can get some clues to this from early written records and I give a few examples below.

The Mabinogi

In the Cymric prose tale, The Four Branches of the Mabinogi, the second branch is titled Branwen, Daughter of Llŷr. In this branch, war between the Britons and the Irish is narrowly avoided and both sides gather for a feast. One of the Britons, Efnisien, jealous of a perceived favour done to another, thinks inside his own head. A rough translation goes something like this:

"No one can conceive of the outrage such as the outrage that I am about to commit now."

He then thrusts Branwen's son into the fire and war breaks out.

This suggests very clearly why we would be concerned about individuals thinking for themselves or thinking by themselves. In later times such thoughts could be attributed to the Devil, or similar.

Homer's heroes

The representations of the heroes in the Iliad and Odyssey of Homer do not contain any references to self-reflective thinking. The heroes act according to the will of the gods, who may speak directly to them. So Odysseus does not make decisions for himself (that is, through thinking things through internally) but rather is informed of the best course of action by the goddess Athena.

The God of Abraham

In the Bible, Abraham clearly hears a voice advising him regarding a journey he is planning. This voice identifies itself as that of the God of Abraham, who turns out to be the one true god, later the one true god of Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

Some final thoughts

I have no real conclusions to offer to this thinking at present- it just seems interesting. There are a couple of thoughts to add by way of finishing.

On a radio 4 programme some years ago (sorry, I made no record of it at the time), three "experts" gathered to discuss the origin of language. Quite early in the program, all three agreed that language "obviously" began internally. This seemed and still seems counter factual. My father, a polymath, including linguistics, was dismissive of the idea and surprised by their acceptance of it.

I'll also raise the point that In contemporary times, an internal voice that is unidentified, or otherwise experienced as not our own is usually seen as symptomatic of mental illness.

Lastly, its interesting to me that from the very early days of meetings and courses on permaculture design here in Britain, great emphasis was placed (and still is, or should be) on a technique known variously as swapping time or speaking and listening, where in pairs, the individuals take turns at speaking and listening in relation to a chosen subject.

I have used this technique many, many times on courses as a way to get individuals to organise their own thinking regarding a particular subject then to take turns in a group circle to feed back and have someone collate the contributions- we're back to group thinking and consensus decision making.

That's it for now. Many thanks for reading and welcome to new subscribers. I'd be especially interested on any comments or ideas you might have regarding the above, particularly examples of internalising the voice, or otherwise, in mythology and literature.

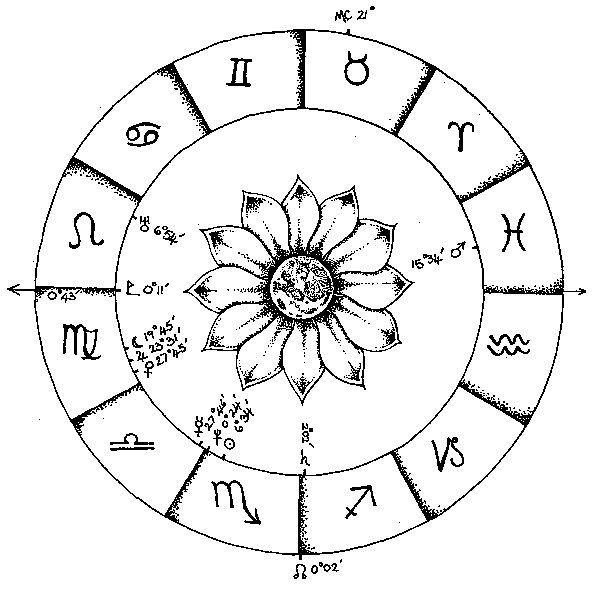

The drawings are mine and represent various ways of mapping consciousness. They are part of a larger study which I will present here on Substack at some point.

Till next time, hwyl! Chris

"Get the tiger into his cage" gives an indication of Vygotsky's position in the then current cultural/social mindset. Perhaps more appropriate for our contemporary wave would be "get the tiger back into her or his forest".

Hi Chris, very interesting and I need to read again, but I remember still on the permaculture course I did in 1991-92 the shock of being put into a circle where we took turns to speak (a new experience) and discovering the power of being heard by others. When I had four or five people witnessing me reporting something I had learnt, or announcing my intention to do such and such, it became far more real than when I just spoke the thought to myself. Typing a comment into a website, as now, has some of that effect but much less. I think we could make much more of the power of this sort of conscious speech - received by people who are actively listening - to reveal truth and find the way forward. People's assemblies is one way to do this.

The course with bill at Ragmans lane was a sunny April 1991. That was the one I did anyway. There may have been a later one?