Rhobell Fawr: the Great Volcano

tectonics, faults, glaciation and uplift: shaping the bones of the landscape.

In order to deepen our understanding of our land and landscapes, we can look from many different perspectives. What's on the surface is most obvious, as in plants, animals and the like and just below the surface we have soils that as gardeners we will take great interest in. Yet under that we have quite literally the bedrock that shapes the environments above, that will influence where and how soils accumulate and develop, that allows for the flow of water downwards, or not, steering streams and rivers, generating springs and spring lines and draining soils or favouring bogs, ponds or pools. Geology- this is where the story of The Real Coed Y Brenin really begins.

above: Mynydd Penrhos from Bryn Merllyn, looking south. The wind smoothed plantation of exotic conifers conceals an underlying complexity of land forms.

To get an idea of the geology underlying Coed Y Brenin, we have to go back in time, a long way back, a long, looong way back! So this is also an exercise in getting a feeling for deep time, that puts our human existence on Earth into just a short blink that in comparison to geological processes, has only just happened. In the case of the geology underlying Coed Y Brenin, we need to go back nearly half a billion years, about 480 million to be a little more precise, to the Great Volcano, Rhobell Fawr1, gulp!

To call that “quite a stretch” is a radical understatment; the first dinosaurs didn't appear until about 240 million years ago. Yes, we could go back still further but while fascinating, the (even) earlier development of the Earth's form and surfaces add little to our particular understanding of Coed Y Brenin today, whereas the repeated eruptions of the Great Volcano, Rhobell Fawr and the massive lava flows and ash deposits that were then eroded over millions upon millions of years, together with the massive faulting, the shattering of the surfaces, their upheavals, folding, overthrows and uplifting and the glaciations that followed much later, provide the structure of the complex landscape that exists today.

Around 490–390 million years ago the continent which would become North America (Laurentia) collided with a much smaller microcontinent (Avalonia) that included parts of modern day Europe along with the landmass that would become Britain. The collision resulted in intense compression, folding, and faulting of the Earth's crust and among other features, produced the Harlech Dome which extended out into what is now Cardigan Bay. The circumference of the dome was volcanically active and produced the huge stratovolcano, a conical volcano composed of alternating layers of lava2 and ash, Rhobell Fawr.

above: Rhobell Fawr looms above Llanfachreth in a photo by Myfyr Tomos. The sign pointing to the left indicates something of the rich deposits of metals.

Estimates of the maximum size of Rhobell Fawr vary at around 30,000 feet (say 9,100 metres) following repeated eruptions of immense magnitude. Over millions of years, the volcano has been heavily eroded, leaving behind the remnants of its volcanic core. Rhobell Fawr now stands at 2,408 feet (or 734 meters). The volcanic core is surrounded by sedimentary rocks, which were deposited after the volcanic activity ceased and is one of the oldest volcanic structures in Wales.

The tectonic forces that shaped the region, building the volcano and other mountains during this collision also resulted in complex faulting. The faulting includes several major faults that criss-cross the region including the Bala, Tanygrisiau and Migneint Faults and a range of smaller faults of various types.

Types of fault.

Thrust Faults: Caused by compressional forces during the Caledonian Orogeny, where rocks are pushed over one another.

Normal Faults: Formed during later extensional events, where the crust is pulled apart.

Strike-Slip Faults: Where rocks slide past each other horizontally, often associated with shearing forces.

This faulting has created a highly broken up and rugged landscape, with steep valleys and ridges running in various directions together with uplifted, rotated or inverted blocks which have in turn influenced the drainage patterns and groundwater flow, with rivers and streams often following fault lines. Its also worth pointing out here that all this intense tectonic and volcanic activity resulted in a wide range of metals being deposited along the rim of the Harlech Dome, including copper, arsenic, molybdenum, manganese, lead and silver althought its normaly known as the Gold Belt3.

above: coinciding with writing this piece, Natural Resources Wales are continuing to fell all the larch on Mynydd Penrhos and as they do so, something of the complexity of the landscape is revealed again, as with the dips, stepped crags and folds here.

What follows all this is a huge expanse of time during which whole mountains (and volcanos) were eroded away. This simple statement conceals the enormity of the process; consider that Rhobell Fawr lost something like 25,000 feet (7,600 metres) of lava and ash. This continues until we arrive in the relatively recent past, a mere 2,580,000 years ago and the Quaternary or Pleistocene glaciation, an alternating series of glacial and interglacial periods that is ongoing, although another glaciation is looking unlikely at the moment...

above: previously hidden crag once more exposed. Interesting to consider that the heather, birch and rowan here are survivals from times long before the plantation.

If we skip to the Last Glacial Maximum, around 26,500 to 19,000 years ago, the ice sheet was thick enough to bury many of the lower hills and valleys, with figures for its depth (or rather, height) estimated at over half a mile (2,640 feet or about 804 metres). If we consider the weight of that thickness of that ice as it grinds its way over the bed rock, its easier to imagine the massive potential to erode and shape the underlying structures of rock and stone, even more so given that each glaciation lasted thousands of years.

So the glaciers can carve out U-shaped valleys and cirques, sculpt complex smaller features like grooves and shelves, smooth and round hilltops and ridges. However, on Mynydd Penrhos and its surroundings those alternating layers of lava and ash were broken up by faulting into blocks that were displaced, some ending up with the bedding planes almost vertical. The softer stones and minerals that formed from the ash are more easily eroded than the lava, granites and basalts, and these harder materials remain as narrow, steep sided ridges like prominent spines.

above: successive steep sided ridges run like spines through the area in a variety of directions, each providing unique aspects and hence habitats.

As the ice melted, it left behind a wide variety of glacial deposits, including clay, silt, sand, gravel and boulders. Some boulders are of considerable size, known as erratics they could be transported on glaciers and ice sheets for considerable distances from their places of origin; my son, Sam, lived in Wolverhampton briefly and showed me an erratic which had been carried there during the ice age from Arenig, a mountain only a dozen miles to the north of us here in Cymru, a distance of about 100 miles (160 Km).

above: erratic in Wolverhampton, delivered from Cymru by Ice (more reliable than Evri…)

Following the thawing of the last ice age about 12-10,00 years ago, further modification continues to take place through what are called periglacial processes, such as freeze-thaw cycles, which contributed to the formation of scree slopes and further erosion of cliffs, crags and outcrops. The vast quantities of water from the melting glaciers carved out deep, irregular valleys and led to the formation of lakes and rivers, which continued to shape the landscape through erosion and sediment deposition.

As a result of melting glaciers and ice sheets, global sea level rose by more than 120m, flooding Dogger Land to become the North Sea, drowning the continental land bridge to form the English Channel and submerging the river systems between Cymru and Ireland. Interestingly there are possible recordings of this last event in the Cymric culture; in the Mabinogi, Branwen's Tale, Ireland is described as at that time only being divided from Cymru by two rivers and there are also tales of the "Drowned Hundreds", Cantrefi that were inundated by rising sea levels and now lie beneath the Irish Sea.

A further consequence of that vast weight of ice in glaciers and sheets was that the crust of north west Europe which is in effect floating on the molten magma beneath, had been considerably depressed. As the ice melted, the land mass slowly rose began to rise again. This rebound or isostatic adjustment as it is termed continues today, with the north west rising by about 1.5mm a year and the south east sinking by about 1mm.

This uplift can be considerable, measured in tens of metres and results in streams and rivers cutting back deeply and steepening their decent, creating gravel and bolder trains that deliver vast quantities of material to the lower regions and leaves it often neatly sorted into gradations from fine to course, in layers and banks or in clay deposits in depressions, such as here at Penrhos.

The result of all this very ancient geological activity and the much more recent glaciation and uplift, is a remarkably complicated geological landscape of steep sided valleys and ridges, crags, shelves, lumps, bumps, hollows, screes, cliffs and clefts. The cloak of forestry today largely conceals this complexity, hiding it beneath the wind smoothed crowns of exotic conifers. Walk under the trees however, where that is possible and you will lose yourself in a labyrinth like landscape of repeated, irregular forms that will continually appear both familiar and unique.

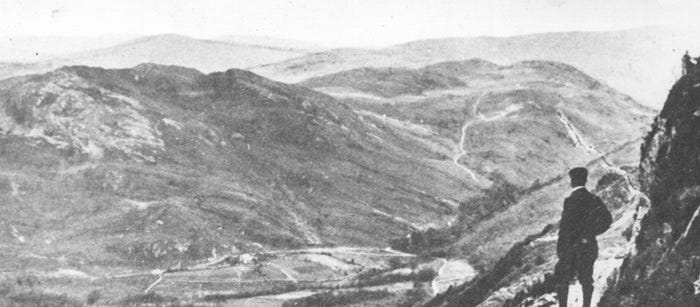

above: Mynydd Penrhos before the plantation of Coed Y Brenin. Detail from an a post card showing something of the rocky complexity of the landscape.

Mynydd Penrhos forms a great fist of rock that now marks the southern boundary of Coed Y Brenin and contains examples of all that complexity squeezed into a restricted form. Here then is the structure upon and within which soils and environments form and in the next piece on The Real Coed Y Brenin I'll look at the proliferation of life that took place as the last ice age came to an end and Britain starts to warm up.

Many thanks for reading. This has been quite a dense piece for me, requiring a fair bit of research to try to fill in some detail to the broad-brush image that I had painted for myself over time and it took a while to get the structure right, hence the delay. There are still some interesting gaps; for example, I would have liked to find out how much weight per square metre a half mile thick ice sheet would apply on the surface, also the temperatures that might be generated there, nor have I found an easy answer to how much uplift has occurred so far and whether it was continuous or sporadic; looking at the cliffs beyond Arthog on our coastline, Lyn has pointed out wave cut platforms that are now at least 40 or 50 metres above current sea level. Anyone have pointers to more detail? Comments always welcome. Till next time, take care. Hwyl! Chris.

The Rh in Cymraeg represents a sound that does not really occur on English. Its actually more like saying the letters the other way around, Hr. Shape your mouth as if you are going to pronounce an H (as in Huh) but spit out an R immediately after the H. I’ve suggested how to pronounce the LL in Cymraeg on Substack before and was going to copy and paste it in but can’t find it and now I am running our of battery on my laptop! Can anyone help?? Fawr is a mutation of mawr, big and is something like the English our in sour, with the single f a v in English, hence like vour.

The lava was mainly made up of porphyritic micotonalite and porphyritic microdolarite which are granites incorporating crystals of various sizes and basalts. For full details, see the work of our local, sane scientist;

Graham Hall, Geology field studies from Lleyn to Plynlimon

an excellent read, available as chapter downloads from Graham's web site: http://www.grahamhall.org/geology/index.html

The abundance of metals in the area obviously attracted a lot of attention over the centuries and I'll look at the mine workings, particularly of gold and silver in another article. Its perhaps worth mentioning that Rio Tinto Zinc undertook exploration of the Mawddach area in 1969-70. More details can be found in the following work:

River of tears; the rise of the Rio Tinto-Zinc Corporation Ltd. Richard West. Earth Island Limited, 1972. Pages 180 ff.

This is also an example of a local estate owner encouraging drilling for copper on his own land in the hope of seeing profits, without seeking planning permission first. Rio Tinto proposed opencast mining of Mynydd Penrhos and beyond to the north (what is now called Mountain Top Removal (MTR) or Mountain Top Mining (MTM). A massively destructive process which is described in harrowing detail in one of chapter of Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt, Author Chris Hedges, Illustrator Joe Sacco 2012 Nation Books ISBN 978-1568588247.

yet more facinating stuff Chris, thanks. It's always humbling to look at the long-term picture. That we call "pre-history"! The bare hills on the postcard (with some riparian "tufts") - would that have been natural or human (timber and sheep)-induced?