The crone follows a narrow path, very gently descending, firm, free of stone or any encumbrance, surfaced with old wood chip, bound by fungal mycelium. The path clings to the contours of the landscape, long sinuous curves then sudden sharper turns, in towards little gulleys where streams collect in pools, spilling to either side into shallow ditches.

Trees and shrubs line the way, a wiggle of blue overhead where the crowns don’t quite meet, an occasional blaze of sunlight illuminating the myriad insects, a lazy hum and buzz interlaced with the song and darting flight of birds and her own slow but steady rhythm with her feet and long stick.

The vegetation is changing from coppiced hazel and chestnut under high pruned oak to more obviously edible species, apple pollards2 over soft fruits, thorn-less blackberries with their long runners woven back into the sides of the path, stands of raspberries, the arching crimson runners of wineberry, trailing dewberry, big leaved thimbleberry, and currants, black, white and red. Here and there she notes where someone has recently added mulch; the blackbirds have moved in already, wildly tossing the debris about in their pursuit of worms and grubs.

She pauses occasionally to have a bite, though the choice is still limited, it being early in the season. She finds the odd red currant bush in fruit and some strawberry, particularly the tiny wild variety which she stoops to pluck, slowly and carefully, leaning on her stick. She delights in their sharp bite.

She is very relaxed. Despite her age, there is an ease in the way she uses her stick to draw a branch towards her, plucks the fruit, a quiet delight in raising it to her puckered lips, a heady fragrance, cool burst of sweetness. Her eyes scan in steady appreciation, her nostrils flare wide, absorbing sensory detail, moment by moment, into her deepening now.

This old woman, her skin wrinkled, yet pale, still wears her pointy, gifted hat, the wide brim protecting her from the glare of the sun. Her dress is light, floats in the breeze. On it, (the dress) green and yellow and brown swirl together, defying the eye in an intricate blur of embroidery, print and appliqué. Something about the complex spiral of the weave draws in and intrigues the eye of the beholder. Her stick is slender but strong, of oak, the top with its thickening root reaches up nearly to her shoulder.

The lazy meander of the path leads eventually to a small clearing, heralded by a growing rhythmical chuckle. Here is a slab of oak laid across two logs for a bench, a pool, a fall of water with stones carefully arranged so as to create a wide variety of sounds, splashes, rhythmic drippings, a low gurgle. The sound, like the ionised air, fills the space. She feels the refreshing moisture, cool on her wrinkled cheek.

She eyes the simple bench thoughtfully. The oak, polished by use, has been chosen for its rippled grain that reflects a flickering light and colour as one passes. It is raised quite high, its edges rounded and at each end are curved branches, firmly fitted, all to ease the seating of elders. She smiles then settles herself down, sighs and rests.

From back the way she has come, tugs of sound that become echoing shouts, increasing in volume, a scream. The old woman gathers up her stick in her right hand, remains seated. Then the sound of footfalls, heavy, running, a frenzied approach. She brings the stick upright before her, clasped now in both hands, waits. The volume increases, the agitation plain. The crone awaits.

Two young men burst into view wearing only colourful shorts, they rush down the path; the dust puffs as their naked feet pound the ground. They approach the clearing, redouble their wrestling race, struggling to surpass each other, close cropped hair, grappling arms.

Then, they notice her and immediately come to a sliding stop, almost fall. One ends up down on one knee, the other on all fours. They bow their heads.

“Crone,” from one.

“Elder,” the other.

She smiles, at the delightful follies of youth.

“Caerwyn,” she says, then more slowly, “and... Gwyndaf, If my memory serves me right.

They grin at each other, are well pleased that she remembers them.

“You've both grown, so much!” She seems to say this so often these days. “Be off, you've better things to do than kneel before an old woman!”

They laugh and thank her and then are gone and the sound of their passing fades, only the occasional yelps and howls, then just the insect hum and bird song.

Time for her to move on, too. She gets to her feet, using the staff with both hands. She's annoyed at the unbidden groan that accompanies the exertion,

then laughs at her own silliness; I'm old, she thinks, why shouldn't I groan with effort?

Just along from the bench the path forks. There's a sign for those who can read it, though it looks just like an old knife stuck in a log. She has reached the environs of the Last Resort cantref.

She enters by the the back door, so to speak, given that there is no door. The trader’s entrance then, for she has indeed a trade. Thus she avoids more public spaces and continues between rows of fruit. Here the plants are given more attention, more space, are carefully pruned, companions about their feet, contained within rings of comfrey.

She meets more choices as the way divides and divides. Each of the paths is signed in some way so as to denote where it leads. The signs, placed to one or both sides of the relevant path, are self evident, plants, objects, sculptures, requiring no words and hence no translations.

One route under an arch of willow which in turn supports a clambering vine has a fine carving of a man washing, the naked body twisted as he strives to reach between his shoulder blades with a cloth, in oak that has seen the sun, silvered with dark cracks. Another has a wooden bowl, angled invitingly and in it a portion of the day’s food. Blue tits dabble in the bowl, from rim to perch to rim as a sparrow vies with them. Further on she laughs at the shining platters from a hard drive placed upon a granite block.

She’s looking for the visitor’s space and comes at last upon the simple model of a circular hut, the thatched cone of roof supported on sticks, no walls. Now she’s close.

She passes a man, old, like herself, sprawled in the mulch with a digging stick, carefully removing seedlings from a wooden tray and replanting them in the ground. The tray is subdivided and he has a skep of compost and a jug of water with him. There is a seat close by where his crutches lean. He raises a seamed face as she passes and smiles, eyes glinting. She nods at him.

When she comes to a crossing path she has a moment of mild confusion but two women in light robes, sitting upon a sunward facing bench, watching a group of young children, look up at her, shading their eyes, then wave.

The children, a gang of five, are concentrated on some matrix they have devised, delineated on the ground by lengths of twigs, the spaces filled with various quantities of objects; three white stones, some acorns, other seeds.

When they notice Dawn they come rushing over, eager to greet the newcomer and she lets them take her hands and grasp the stick as they steer her in the right direction. They babble like a brook around her. She asks their names and what they are doing but they are more interested in her than in her interest in them.

“We know who you are! We know who you are!” a waif with blonde plaits exclaims, unable to contain her excitement. The others agree.

“Do magic!” cries a tiny lad whose little hand she has to stoop to take.

“Magic!” the cry is taken up, “Magic! Magic!”

The crone laughs; perhaps retaining the pointy witches hat was a mistake! No matter. She reaches first within a pocket then deftly to the tiny lad's ear and with a flourish reveals a smooth, shining pebble of quartz. Oh, how the young ones squeal in delight!

The two women draw up to retrieve the flock. Their robes are light and full, concealing most of their skin, floating in the breeze. The colours are green and blue like flames, intricately patterned and painted; Dawn recognises the style of Schools Out cantref; itinerant teachers then. One of them straightens the headgear of a child, arranges the material to cover the neck and shoulders. The other speaks to the children in mock admonishment.

“Let the elder be, now. She has important things to do.”

“All things are important,” Dawn says gently and she bends slowly, steadying herself with her stick and arrives at the level of the little ones, looking each in the eye as she goes on, “And all of you are important.”

She tousles the smallest head and rises.

“As are you, too, sisters.” She says to the women. They are a deal less than half her age. One has a scar on the left side of her face, running from the point of her jaw to the bridge of her nose. They smile at her openly, without embarrassment. She is pleased and lets them see it. Then, sure of her way now, she turns from them. As the school returns to its bench the children question their tutors.

“Can she heal an INCO?” she hears one ask.

It is enough to put a slight pause in her step and she has to steady herself with her stick. She covers the physical stammer by raising her free hand to her hat and pulling the brim downward, casting her face into shadow. Can she do it? It is a worry already hanging from her inner tree, waiting for attention, some-when.

The bushes draw back, opening onto close-cropped grass that surrounds the visitors' accommodation. The building is like the model in that it has a thatched cone of a roof supported on larch posts. These she sees have been grown somewhere prone to turbulent winds, for they twist and almost spiral. Unlike the model there are some walls, of plaster or mud perhaps, washed a pastel shade of blue, shaded by the wide overhang of the roof.

Outside, by the door-frame carved with a spiral of ivy, stands a man, old and bent, waiting for her, his bedding roll lying in the shadow of the wall. She remembers hearing that he will no longer sleep inside. His face is a mass of lines and wrinkles, sun burned, wind marked. He grins, showing the numerous black gaps in his teeth. So he has thrown away his plate again. This worries her a little.

She muscle reads him. The forehead is drawn into furrows and, despite the grin, below the eyes are anxious tremors. The tension in his calves locks his knee joints which in turn tilts his pelvis which in turn puts a curve in his spine, a stoop to the shoulders, a forward thrust to the neck. Everything connects.

They embrace. The old man immediately begins to shake. She draws back, holding his arms at the elbows, puts a big, delighted grin on her face. He starts to speak, his voice now trembling with suppressed fury.

"What the bloody hell's going on!" He stutters, spitting.

The crone, Dawn, prompts him.

"What the bloody hell's going on, Spicer?"

Many thanks for reading. Heartfelt thanks to permaculture designer, Chris Evans for permission to use some of his photos of his work in Nepal, where many people face challenges that dwarf those of our own, here in the rich west. The times are coming when we too will be forced to act, hence the imperative to learn their lessons and prepare now. Pictures without footnotes are from our own gardens, here in Cymru.

Thanks again and please, do leave comments, suggestions and the like- they are greatly appreciated. Hwyl! Chris.

Level path through forest, Nepal. Picture by Chris Evans. In the times of Konsk, indigenous people of various lands were invited to the Old Country to provide specialist knowledge and training in dealing with the increasing ravages of global warming.

Coppice and pollard apple orchards were originally conceived by the permaculture designer Phil Corbett and were developed from ideas that arose at Rothamsted, a plant research centre responsible for much significant work. Practical trials of coppice and pollard apples now exist, pioneered by the permaculture designer, Chris Evans and a video of his work is available here.

Agro Forestry with contour access and terracing, Nepal. Picture by Chris Evans.

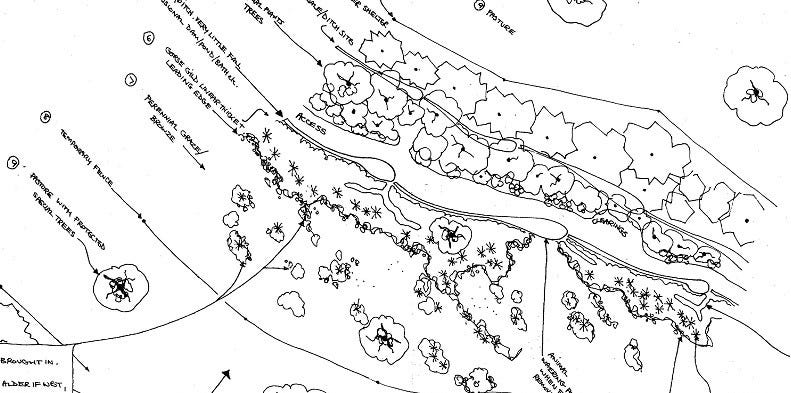

Extract from one of my designs for productive boundaries including close to contour access path and water management via a ffos dyfri (a watering ditch).

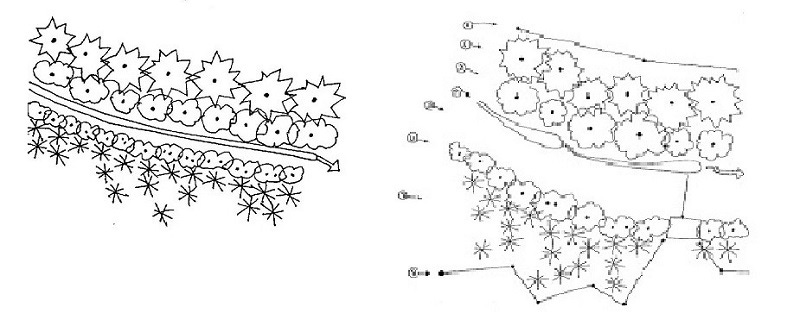

More of my designs for productive boundaries, the one on the left done with David Holmgren, co-founder of permaculture design. Designs do not have to be complex to be effective.

Living fence with contour path and young human, Nepal. Picture by Chris Evans.