To the north of Mynydd Penrhos a conifer clad hill appears to rise in a gentle mound but the smooth curve of the crowns of the trees, as with many of the hills of Coed Y Brenin, does not reflect the remarkably complex topography of the landscapes beneath the canopy. Clear-felled in the mid 1980s and subject to the Forestry Commission's “do nothing” approach, it has been an almost impenetrable thicket for over thirty years

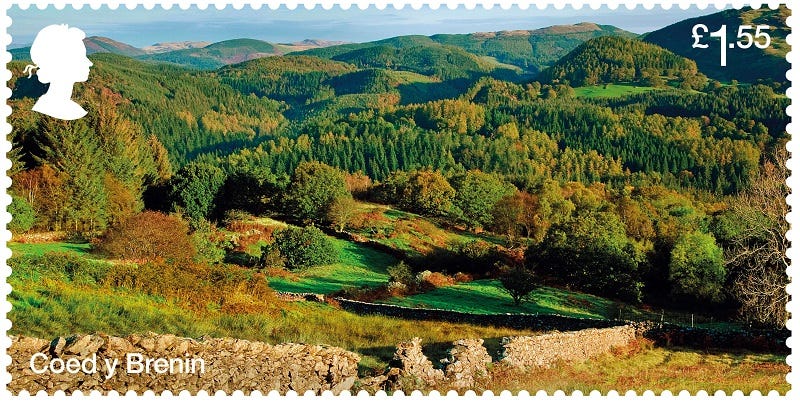

above: a view of Coed Y Brenin on the Royal Mail series of stamps. Hold on though, is something missing? Read on to find out.

NRW began the process of opening it up by cutting harvester tracks through it and conducting machine thinning as best they could, though some parts were not reached. Now it is possible to walk beneath the tall thin trunks and light floods in from the open canopy, greening the forest floor with mosses. Where the light can come in, so too can the wind and parts are impassable again due to windblown trees. Where you can walk freely you will find in the landscape a wonderful complexity of sudden rises and descents, ridges and hidden valleys, shelves broad and narrow, dips and hollows filled with rushes over peat. I try to imagine it without the conifers and can see where there would have been useful grazing in no doubt beautiful, flower strewn pasture and ffridd.

This alone though is not what makes Bryn Merllyn unique in Coed Y Brenin and probably beyond. Merllyn, Mer-Llyn, means something like stagnant pool or lake and as the name suggests, there is indeed a small lake in a depression between two ridges, right at the very top of the hill. No streams feed this small lake and it has no visible exit for water. Sometimes it is full of water, lying in a gentle curve and fringed with rushes, sometimes it is empty and you can see where in the past, water voles have dug networks of tunnels in the peat.

above: the merllyn at the top of the hill- not as wet and large as I’ve seen it but still strange and mysterious.

As with many peat bogs, stories cluster about them; they are old, some 9000 years, forming after the retreat of the glaciers, in the depressions left by the great blocks of ice that took centuries to finally melt. They were places favoured by Druids and no doubt this mysterious Merllyn, that would grow and shrink as if with a will of its own and with its unique location held special significance for them; woe betide those who disturb its quiet,, sacred presence!

above: the Merllyn again, in one of its drier phases.

In our early days here, we felt it was important, vital even, that we learn as much about the watershed around and above us as we could. Ultimately this area supplied us with the water that we and our place1 depended on, draining into the main stream that ran through the holding and infiltrating the soils that sustain life.

So we would make opportunities to explore, wandering the forestry tracks for hours, at that time between dense, enclosing conifers,only a thin strip of sky above, at first without meeting a soul and never a view out, the trees being so crowded and unmanaged as to be impenetrable. I would push into the thickets, finding less difficult routes along the old walls or hedges, their original trees, hazel, ash, oak struggling to survive, reaching thinly up for the light between the enclosing evergreens. Using photocopies of a map from the late 1800s, held in the archives in Dolgellau, at a remarkable scale of 24 inches to the mile, that showed almost every tree, I was able to find the ruins of barns and houses. This map also showed a pool at the top of Bryn Merllyn.

I first stumbled (almost literally) upon the merllyn in the early 1990s. Clear-felled in the mid 1980s, the hill was a dense, almost impenetrable thicket. I'd followed a fence line upward, forcing my way through the branches of the young trees, not an easy task that left me with many scratches and required regular pauses to retrieve my cap. After much exertion I crawled under low branches up a slight incline and then down the other side and quite suddenly, there it was, a curve of water hemmed in and darkly shaded by the surrounding conifers, a light, low mist hanging just above the surface. I was frozen, in awe and remained so for some time.

The second time I made the then difficult ascent of Bryn Merllyn to visit the lake, I couldn't find it...How could I fail to find a lake at the top of the hill! After a fruitless, blundering, scratching search, I gave up and retreated. This only added to its mystery and it took several attempts over several years before I was confident that I knew where it was and how to get there. It was on these subsequent visits that I realised its changeable nature, how it would shrink or grow according to the seasons and rainfall.

above: the quarry after the first enlargement with the stone crusher. In this phase, the forest edge has not been touched- note how the branches reach the floor and there are deciduous trees amongst the conifers, all good protection against the wind.

Sometime in the past of Coed Y Brenin, the Forestry Commission had started and operated a small quarry on the south side of the hill, to provide hard core for their tracks. We had found this quite early in our wanderings as of course it bordered a track and was hence accessible. In the 1980s the quarry was much overgrown with trees, simply a gate leading into a small, level area with a face cut into the rock of the hill only some 40 feet in height (say a dozen metres). I wish I'd photographed it then but in those days, pre-digital cameras, film was expensive2.

Without warning, the quarry was enlarged by the Forestry Commission in the early 1990s. The first we knew about it was hearing an explosion and feeling the tremor run through the land. A fortnight later the planning application appeared in the local newspaper. In fact, not even the application was necessary as the Commission had a Crown Exemption and could basically do pretty much what it wanted.

above: Coed Y Brenin from precipice walk. I couldn’t find the exact place that the Royal Mail stamp was taken from. In this picture, Bryn Merllyn is to right of centre, the dark hill before the more distant ones. What’s that on its left flank, that doesn’t appear on the stamp? Could it be the quarry? Someone has made clever use of an airbrush for the Royal Mail…

This first expansion was relatively minor and did not effect the surrounding vegetation. Nothing much happened there for some time accept for the usual odd events when a newly promoted forester took over management, effecting small but noticeable changes as part of making their presence known. So one had the gate moved from the south side to the west and the next had an earth bank constructed along the track sides, enclosing the site. It wasn't until Cyfoeth Naturiol Cymru or Natural Resources Wales (NRW) came into being that anything significant occurred.

NRW took over from the Forestry Commission, Wales in 2013, amalgamating forestry with the Countryside Council for Wales and the Environment Agency, Wales. This merger caused considerable upheaval and required several years before the reorganisation began to function in any sort of coherent way and deserves looking at in more detail, but not yet.

above: enlarging the quarry under NRW management. The boundary has been clear felled exposing unprotected, over tall, crowded trunks. Some have already blown over to the left. The machine is scraping the surface clear of soil, prior to blasting.

The first major expansion of the quarry came in about 2016 when new promotions were accompanied by new job titles- Foresters had now become Operations Managers, an ominous development, suggesting a change in attitude towards the forest. One of the new Operations Managers clearly needed to make an impression so had the gate moved from the western side back to the southern side, probably unaware that this is where it had begun its life and a fence appeared on top of the enclosing bank.

More significant was the enlargement of the quarry. This required first clear felling a broad sweep of land to the north. The established forest edge, a mix of conifers and hardwoods with branches down to the ground, were felled and a new edge established some 30 metres further north. This new edge revealed the closely packed, tall, bare trunks of the unmanaged stand.

I'd been fortunate enough to attend an Advance Permaculture Design Course led by Bill Mollison himself, co-founder of Permaculture Design, in the very early 1990s, a quite brilliant course packed with gems. When talking about forests, one thing Bill emphasised was the crucial importance of forest edges in protection from the wind and that we interfered with them at our peril, or rather, at the peril of the forest. I was to see examples of the consequences of failing to observe this simple lesson repeatedly here in Coed Y Brenin.

above: exposed to the prevailing south-westerlies, the weak trees blow over all too easily.

The newly exposed trees have grown up supported by their surrounding siblings; they have no experience of wind, their roots have not had to dig deep and cling to the rock beneath the shallow soil, they have not developed supporting buttresses, thickening on the leeward sides. Unmanaged, hence unthinned trees are even more at risk, crowded for space with limited areas for their roots, branches only towards the very top of their trunks hence plenty of space for wind to howl into and through the stand below the crowns. If the newly exposed stand is facing the predominant wind, where the gales come form, the results are all the more inevitable.

This enlargement was followed by more blasting and an expansion of the worked area. A second enlargement took place in about 2018 and the worked face is now within about 30 metres of the merllyn. It seems inevitable that if this continues, the lake will at some point be drained.

above: once the wind had worked its way over the ridge, it wreked havoc in the stand below and has now begun to throw down even well spaced trees on the right hand side of this track, which previously had been sheltered by the block on the left.

Prior to this second enlargement, on one of my walks I found a few NRW officials at the quarry and got into a conversation with them. One of them turned out to be their geologist who was assessing the situation. He didn't know the name of the hill and being English, when I told him, I had to translate it for him. I expressed surprise that he had never actually climbed the Bryn Merllyn and knew nothing about the lake on top of the hill that he was about to blow up.

With my local community councillor hat on, I attended one of our council's meeting where we had invited another NRW Operations Manager to attend in order to ask questions- my parish includes all the Core Block of Coed Y Brenin and beyond. Fair play he was very good, answering many questions form the various members to the best of his ability.

Towards the end I mentioned the quarry and the fact that it was now very close to draining the merllyn. He looked straight at me with a decidedly blank stare and said simply “Mae genon ni'r caniatâd”, (“we have the permission”). I asked him if he was concerned that this unique feature of all the hills in Coed y Brenin would be lost and, with the same stare, he said again, “Mae genon ni'r caniatâd.” End of.

above: the quarry in 2022, all the trees to the right along the ridge now gone. The top of the quarry face is only some 30 metres from the merllyn.

How this can happen in a National Park, in an area where the extraction of aggregate is prohibited by the Park, in a country where the Future Generations Act explicitly requires the preservation of landscapes, by an organisation whose remit includes safeguarding the natural resources of the land, is both a mystery and a bit of a tragedy, that the officials making up the new body do not seem to care about the landscape in which they work.

Perhaps a clue lies in the translation of the name. In my days as a tutor at Coleg Meirion Dwyfor, Dolgellau, a bilingual college with first language Welsh, resources was translated as adnoddau, yet in the Welsh of NRW it is cyfoeth, a word which is generally translated as wealth, a subtle distinction...

Many thanks for reading. Please feel free to share widely and as always, comments and suggestions are most welcome.

In teaching permaculture design or giving guided tours of Penrhos, I would refer often to “our place” but I would point out my emphasis- it was our place, not our place. This small difference contains significance, for it is our place, in that it is the place where we fitted, not the place that we owned, as in the end, ownership of land is an illusion of capitalism. Interestingly, the longer we have been here (now, in 2023, 37 years) the better the fit as we have adapted to fit the place and in a sense, the place has also adapted, to better fit us.

In the 1980s, it cost me about £15 for a film of 36 pictures, including development and mounting as cardboard slides, so I could show them with a slide projector and use them as examples in my teaching. In the early eighties Lyn was working for £40 a week (I know, sounds mad now...) so I would have to think very carefully before taking a picture. It wasn't unusual for a single roll of film to stay in my camera for a year or so, and when the mounted slides came back, some would be underexposed or there'd be drops of rain on the lens, or my thumb....Now I can easily take that many on a single walk- how things have changed, eh?

Always enjoy reading your stuff Chris, diolch fy ffrind