I return to The Real Coed Y Brenin and I've jumped forward in time, mainly to get the current state out there before its too late and I'm just moaning after the fact. However, I will need to go back a bit first, to see how we got to where we are now. All will become clear!

In the late 1990s, the Forestry Commission, Wales, held a public meeting in Neuadd Y Pentref Ganllwyd, our local village hall in Ganllwyd which I attended. The FC Liaison Officer, Aled Thomos, a local who had steadfastly refused promotion in order to stay local, made the presentation. It came as something of a surprise; basically, the Forestry Commission, Wales, completely reversed its original policy.

Coed Y Brenin had always been intended as a production forest, growing timber for a wide variety of purposes. Originally geared to the vast demand for wood during war time, a range of other products had appeared, such as pit props for the rapidly enlarging coal industry, sawbars for boards and pallet wood, fencing materials like stakes and rails and wood pulp for the paper mills. Note that this does not include timber for building purposes. Why? It had long become obvious that conifers grow extremely quickly in wet, temperate climates compared to their colder countries of origin and hence produce poor quality wood that has little structural integrity, with some exceptions, which I will get to, eventually...

All this was changing. Following the Second World War, Europe settled down and another war seemed increasingly unlikely. The mining industries began to switch from wooden pit props to hydraulic jacks. The growing environmental awareness and environmental legislation meant that the preservatives, the only thing that makes softwood stakes and rails last, fell out of favour- previously, manufacturers had promoted stakes as lasting up to 25 years, such was the potency of the biocides used, whereas today you pay a premium for a guarantee of just seven years. A further blow was that paper mills became required by law to take a certain amount of recycled paper annually, meaning that at some point every year, the mills would close their doors to fresh cut timber.

Added to this was the collapse of the Soviet Union, the USSR, (yes, collapse, of a large, modern, super-state, remember? It can happen!) and its disintegration into separate states, all of which were desperate for western cash to kick start their new independent lives. Timber from eastern European forests was an easy and obvious source of immediate wealth and soon huge amounts were appearing at British ports and it proved far cheaper for the North Wales sawmills to buy baulks of timber directly off the docks than from the forests literally just down the road from them. Timber prices had been low generally anyway but now the bottom fell out of the market and the Forestry Commission, Wales, found itself managing some 19,000 acres of mature and over mature conifers, with a large workforce to pay and almost no market for their products, and that was just Coed Y Brenin..

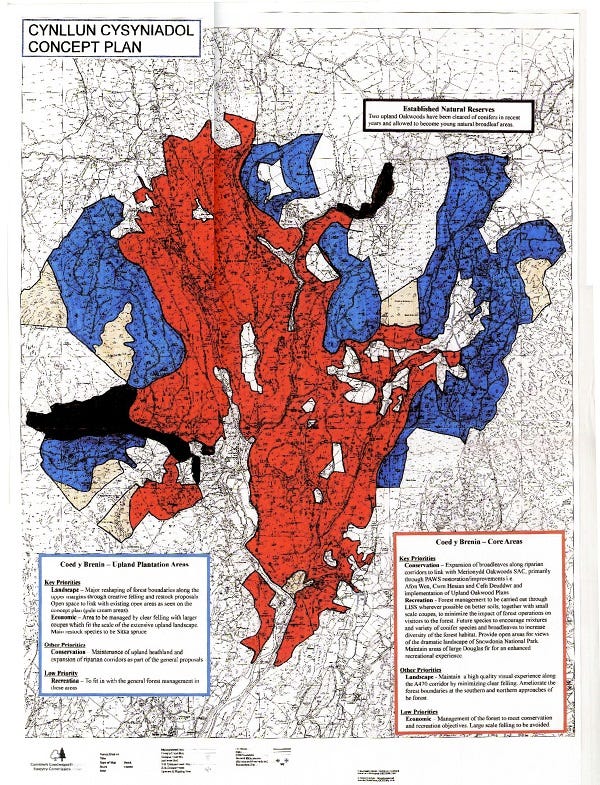

.above: map showing the redesogned forest- blue areas were to be retained as productive forest, red areas to go over to recreation, conservation and tourism. Management to be low impact silvaculture as in, do nothing.

The result was a massive change in direction. Who actually came up with this scheme I don't know, presumably some clique high within the Commission. Aled explained to us that Coed Y Brenin would be switching away from production and moving into conservation, recreation and tourism, with the funding for this coming from European grants. Wales, classed in Europe as a deprived country, was open to considerable amounts of cash from the European Social fund, to name just one source.

In particular, the Commission was able to tap into Access Funding, European money that was given to increase access to the countryside through the creation of new paths, mountain bike trails, disabled access, visitor centres, car parks, toilets, signage and the like. This approach proved so successful, in terms of funding, it was continued by Natural Resources Wales when they took over from the Commission in 2013.

How much money this amounted to in all, I have no idea but I do know that between about 2015 and 2018, over a million pounds of NRW money (from Europe) flowed through the small, Signs Workshop based in Ganllwyd, just for producing signage in Wales, for all the new access opportunities and the switch from Forestry Commission Wales to Natural Resources Wales

above: standard NRW signage.

The result was an organisation with more Mountain Bike Rangers than Foresters, who knew more about maintaining a trail than thinning a coupe. Aled told us that we'd seen the last of clear felling in Coed Y Brenin (sadly not true) though they would continue to fell small patches just to keep some experience going within the workforce.

From observation, it was decided that it was not necessary to replant as there was sufficient seed (of conifers) in the ground to make natural regeneration effective, so they would be adapting a “do nothing” approach. In fact, replanting was often carried out anyway, mainly Sitka and Norway spruce. Most of the core block would be treated this way, favouring recreation, conservation and tourism; only the outlying plantations to the north and west, more monotonous, monocultural stands, would still be managed for production.

It came as quite a surprise and it was only as time went on that the flaws in the new approach began to show up. One crucial point to make here and its a lesson that could have been learnt from the collapse of the Soviet Union, is that knowledge that you would think was secure and embedded in an organisation or society, can fade and disappear within a single generation. In the case of the Forestry Commission Wales/NRW this is quite striking; what seems to have been lost in particular, is the awareness of the dangers of fire, the importance of regular thinning and knowledge of local wind conditions and topography when deciding on clear felling.

What I want to look at here, though, is how the switch away from production to tourism and conservation and in particular, the “do nothing” approach and the loss of practical knowledge regarding the safe management of plantations, has led to a situation that is over ripe for both sudden catastrophic failure and the slow, almost imperceptible descent into decay.

So what happened? When we arrived in 1986, the bulk of the northern part of Mynydd Penrhos had just been clear-felled, leaving a vista reminiscent of the Battle of the Somme or other appallingly destructive landscapes. The land was treated to the sort of rape and pillage that I have described before (Tree planting and carbon offsetting), and was replanted with a second generation of conifers. These plantings were then in-filled by self-seeding conifers (mainly Western Hemlock, more of which later), birch and a few oak, meaning that the trees were really packed in.

above: unthinned coupe. Note the great variation in diameter of stems, many of which are dead or dying from being shaded out and the debris, or fire load, accumulating on the ground. I could walk for several miles taking pictures like this and this…

This is not necessarily a bad thing as it gives the forester plenty of choice at the first thinning stage, usually at about 7-10 years. However, if you intend to “do nothing” then this has significant consequences. Such a full coupe will reach thicket stage, when the trees shade out all undergrowth and accelerate in growth, very quickly but it will also stay in that thicket stage for much longer. During that period, many, indeed most, of the trees will die over time, shaded out by their neighbours. They will also grow tall for their girth, as they all race for the light.

This means that the stand of trees will contain a very large number of dying or dead trees that will dry out and eventually fall but may remain standing or leaning (hung up in other trees) for many years, so there is an accumulation of dead wood on the forest floor as well as standing dead wood, drying out.

In a managed plantation, the thicket stage, which is the high fire risk time, may only last five or ten years, as the workforce makes successive thinnings, removes the dead wood and opens out spaces for the remaining trees to grow into. However, in the “do nothing” approach, the already grossly overcrowded stand remains in the thicket stage for twenty to thirty years; indeed, parts of this previously clear-felled area are only just becoming accessible after over 35 years.

above: saplings planted at two metre intervals and never thinned.

above: the same trees looking up. Notice the tall, slender trunks and that the trees have failed to close the canopy, having been left in the thicket stage too long. They’re really dwarf conifers on very tall sticks. Many of these are in fact dead, shaded out in the race for light.

A further consequence is that the trees grow fast throughout the thicket stage, competing with each other as they race up for the light. On parts of Bryn Merllyn, to the north of the Core Block, the trees have reached some sixty feet in height (OK, 18.274 metres) yet many of them have less than two metre diameter root space and remain very slender. This makes them particularly liable to wind-blow and breakage.

above: unthinned coupe left exposed on the windward (western) side by clear felling. Notice the snapped trunks and the wood left where it fell, just the ends cut off to clear a track.

Where the wind has got in to these stands (often through inappropriate felling, leaving them exposed to the westerly gales) there are some very good hints at the sort of destruction to come if the situation is not remedied. Another hurricane force 12 event in the Irish Sea, such as we experienced in February 2016, after prolonged and extremely heavy rainfall that saw hundreds of trees blow down may well result in thousands blowing down, or even tens of thousands; or indeed, the lot...

above: Moel Dolfrwynog-clearfelled on the western slope leaving the top of the hill un-cut. Exposed to the prevailing winds, almost the whole coupe has been flattened.

In a way, the “do nothing” approach just formalised what had been going on, or not going on, anyway. Having wandered the forest from the early 1980s, it is amazing how little has been done, particularly in the Core Block. Here we have coupes that may have had one or maybe two thinnings and then have been largely left to get on with it for the next fifty years. Many of these, like the Douglas Fir that greet the visitor at the south end of the Core Block, are well beyond their commercial maturity, now so large that the mills do not really want them (too big to easily manage), that have achieved about the maximum height that the environment can support of about 100 feet or 30 metres, given the shallow soils that are often either waterlogged or dry and the regular winter gales.

The forest's fuel load has also been increased by the failure to clear fallen or hanging trees. Back in the day, a contractor or two would work their way round the forest once or twice a year collecting fallen timber for re-sale, usually as firewood but this has always been an expensive operation- its far cheaper to take a whole coupe of trees at once than muster more or less the same equipment and workforce merely to deal with individual trees from here, there and everywhere. It also used to be possible to buy a “ticket” from the Commission to scavenge wood from patches of clear-fell (I benefited several times from this) which again served to reduce the fuel load. The tightening of Health and Safety legislation ruled this out.

above: Track cleared off fallen trees but the wood just left.

But since the switch to recreation/conservation, fallen trees are cut through where they block a path or track, but the wood is not collected and is just left on either side for “habitat”. Trees that fall or hang up within a coupe are ignored. How much “habitat” of this sort is actually useful is up for debate- at the moment it seems to be simply more fuel drying out waiting for the great conflagration or food for honey fungus...

Now, turn the larger part of the plantation over to tourism and build barbecue sites here and there. Add in the rise of wild camping, van living and the fact that everyone who camps out in the forest (illegally), seems to want to have a fire. Then make sure to leave plenty of stacks of timber lying about and kill most of the rhododendron plants that infest the forest through stem injection leaving the dead stems to dry out. Layer on top of all that global warming and the likelihood (inevitability) that temperatures will continue to rise, more or less every year for decades to come and it seems pretty obvious where we are going to end up without some really radical action.

above: rhododendron killed by stem injection. Being an exotic and toxic, decay is extremely slow. These dried out stems provide “ladders” for a ground fire to climb up into the canopy.

Fire then is the first and most destructive of The Three Fates that await Coed Y Brenin and I will look in some detail at the types of fire and the other fates next time. Following that, I'll suggest some of the things that could be done to get us out of this mess.

Many thanks for reading. Please keep your comments coming in- they are always useful!